By Jay Hudson

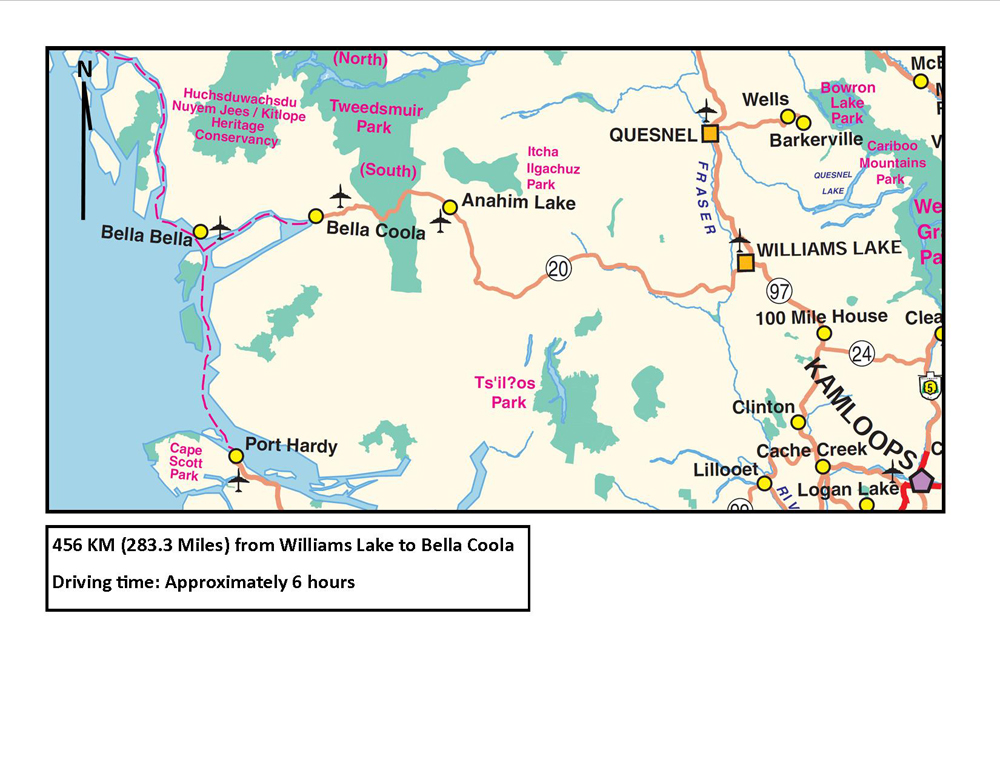

The British Columbia Canadian border guard waved me over to the side of the entry station with a slight scowl on his ruddy face that summer day in 1984. I can’t say as I blame him. I must have looked like a hippy in my old beat up Datsun station wagon. I had been wandering from Ogden, Utah for three days and the back of the wagon looked like a disaster area with supplies, a rumpled sleeping bag along with bicycle parts laying helter-skelter. I didn’t look much better with bedraggled clothes, a beard, wild hair, and probably cookie crumbs stuck to my mustache. Once I explained that I was on my way to Williams Lake to ride my mountain bicycle 456 km to Bella Coola over the Chilcotin territory, they let me into the Queen Mother land; reluctantly.

Williams Lake

I parked the car in Williams Lake, gave the keys and my wife’s phone number to a fellow from the road department. I saddled up, and headed west in 92 degree heat. The idea was to cross the Fraser River while staying on Highway 20 for five or six days. This leisurely ride would bring me to the point where Alexander MacKenzie reached the coast after crossing the continent some 10 years before Lewis, and Clark. There would be mountains, rivers, valleys, grizzly bears and unanticipated mini-adventures along the way. Once in Bella Coola, I would catch a twice a week bus back over the rutted, steep, rocky dirt road.

From the outskirts of William’s Lake the paved road turned uphill then dropped to Sheep Creek Bridge across the Frazer River. As I peddled up Sheep Creek Hill I used all 18 of my gears to make the 1,200 foot climb. Topping out, I entered Belcher’s prairie knowing a few hours of flat riding would renew my energy. There was a sign at Hanceville about 40 miles west of Williams Lake that warned travelers not to attempt the road without good brakes and emergency provisions. It was talking about autos as no one has ever made the trip on a bicycle. Trailers were not allowed. I left pavement at Hanceville peddling onto the best stretch of dirt I would see for days, and the last of pavement until the Bella Coola valley. I was taking a chance on the road because the history of this old horse trail since it was pushed west in the 1860’s was one of bad weather and bad surfaces with long periods between help. Cell phones were somewhere in the future so I knew I may be laid up beside the road in a tent waiting for dry weather or an occasional rancher for help. I gambled that July 1984 would be good to my 49 year old body.

The Chilcotin country was sparsely populated with a history as a tough land calling for tough men and a few very strong women. Men eked out a living from the land when it let them. Scattered ranchers sought the comfort of few, and far between stores while Merchants counted on these rough men to keep the store open. Sightseeing travelers were scarce as the road wasn’t bulldozed to Bella Coola until 1952, so unless you lived in the area, were visiting, hunting or fishing, there wasn’t much reason to risk the trip.

Alexis Creek

Alexis Creek was big enough to have buildings on both sides of the road with Pigeon’s Old Fashioned general store the center of activity. Upstairs from the store was a community hall demanding you enter, and have a look around as it was the only thing of interest in town. The folks in the store would send a letter for you, sell you fishing or hunting licenses or fill a box with food stuffs and staples. Several dirty old vehicles were parked outside some in such condition that I wondered if they were abandoned. A maroon Chevy sedan caught my eye because it looked like it had just gone through a car wash or a deep creek. A red mailbox hung from the side of the store near the ever-present store bench inviting anyone to sit a spell and spin a story.

The road tread changed every few miles, and although it could be rough with ruts, stones or water, it was rideable. If I was lucky, my spare parts could keep me going without having to send back to William’s Lake for replacements. The weather held. Although I thought I would be seeing wildlife, few animals or birds were in evidence. Running water was always a welcome sight giving me an excuse to dismount, and soak my hot feet. Traffic was not a problem as I could ride for hours without seeing another person. I must have been viewed as a crazy outsider with my saddlebags, shorts, and long socks. Outsiders had never been that welcomed in the Chilcotin but I never felt I wouldn’t be helped if I needed it; if only to keep me moving.

You could argue the title “Highway” 20, but you couldn’t argue the tenacity of the people depending on it to survive. The time I spent growing up in the north plains country of Montana taught me that those who didn’t survive the country were the ones who couldn’t use whatever was handy to fix whatever necessary. These were people that could sit out the night in a cold broken down car or who could make a big story out of the smallest of hardships. I admired the people of the Chilcotin. It hurt a bit, though, when I parked my bike up against a buck rail fence at an isolated old home, entered a café created out of the living room, ordered a slice of apple pie, and no one paid me the least bit of attention. Even Montanans would have said, “Howdy”, and probably inquire what I was doing on a bicycle so far from town.

Between Alexis Creek and Redstone a small log red roofed store surrounded by another buck rail fence that looked like a good place to stop. The store sported a gas pump with a long handle to manually fill the glass reservoir for gravity feed. The pump sat between well-worn tire marks on the grass. It brought back memories of when I lived in a log house with the same kind of pump where my Dad and grandparents also sold a few supplies. It was my job to fill the reservoir and let it gravity feed into the car’s gas tank. That was in 1947 on Highway 2 at the bottom of Glacier National Park in Montana. I rode by the Redstone Cemetery, and wondered about the people buried there and how they had died in this harsh country. The graves had little picket fences around them. Some of the grave sites needed care but I guessed that after a few years no one remembered much about some of the owners.

Chilanko Forks

The road got rougher. Riding now demanded constant rock dodging while easing my way across minor washouts. The country was green, the sky clear and the wind calm as I peddled on toward Chilanko Forks store on a much abraded road. I had made letter arrangements with the store owner Ron Morrow to camp in the back of his place. I looked forward to some conversation, a beer, and a hot meal made up by a real cook.

The ride through Bull Canyon on the way to Ron’s was enough to make me want to camp early, but the idea of a cold beer at Ron’s store kept me going. Ron showed me where to put up my tent as we talked about my trip. I asked him what was happening with a group of locals sitting on a fence across the road while a fire shot flames, and smoke into the air on the plateau just up the hill. Ron said that it was a yearly event. The locals set the fire, called it in, then sat on the fence waiting for the government to hire them to go up the hill, and put it out. Nice work if you can get it! I filled up on supplies from the store, had a good nights sleep, and saddled up for the next stretch of road heading west. There were no early morning signs of weather trouble ahead. Because there were no weather forecasts, you had to use your eyes, and nose in place of the newspaper.

At Tatla Lake the scene was just what you would expect from the Chilcotin; an old two-story house with a porch where a sign stating AISCAMIVE (?) hung was complemented with a nearby rusting hay rake, a buckboard, and the lake in the background. Snow covered the mountains in the distant north making for a picture postcard scene. I heard later that the house was used as a dorm for a nearby long closed school.

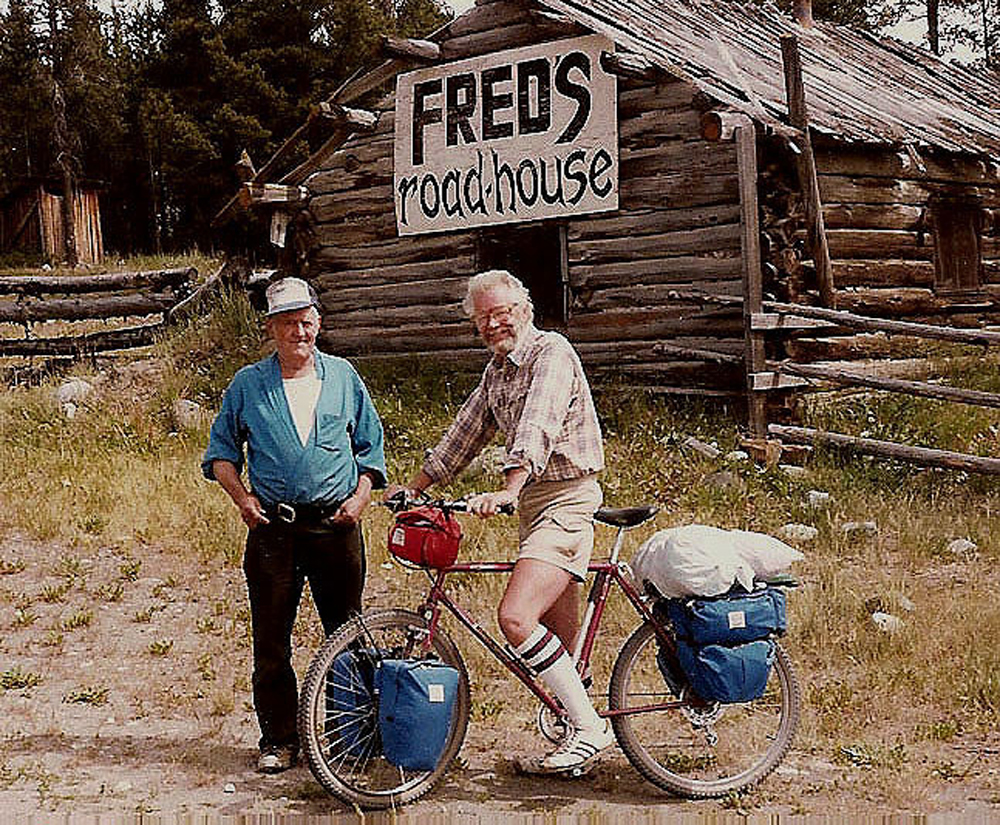

Fred’s Road House

I pulled off the road at Towdystan to admire a great white sign calling out FRED’S ROAD HOUSE. It hung on a barn long out of use when up walked a fellow who wanted to know what in the world I was doing on a bicycle. He introduced himself as Fred Englbertson. He wore his weathered baseball cap at a rakish angle, a night shirt stuffed into his black everyday work pants with a huge belt buckle pushed halfway to his right hip. I was sure that he saw me coming, threw on a pair of pants over his nightshirt, and came out for a meet and greet. I got the definite feeling that here was a man that was self sufficient, could fix a tractor or my bike, and had a few stories to tell while he worked. I was also sure that everyone in the Chilcotin probably knew him and had a story about him. Fred invited into his home for a cuppa where his massive living room was filled with hunting trophies from his guiding days. It turned out that he had never left the Chilcotin until he was in his 50’s when a client invited him on an African Safari. It was strange to see a Cape buffalo, and a Thompson’s Gazelle hanging beside a grizzly. Fred said he didn’t like the custom of having the Africans carry his gun, load it and hand it to him for the kill so he hauled it around Africa just like at home in the Chilcotin. He said his best memory of the trip to Africa was not of the hunt but the parties in Paris.

Flying

The weather held as I pushed west in a fresh pair of socks, a candy bar pulled out of my pannier, and a plastic bottle full of fresh cold water. I passed a roofless abandoned log cabin with a bus stop sign nailed to the lintel. There was no door, just two broken rusted hinges. I wondered if this was a joke or did the Chilcotin run horse drawn buses in the old days. Nimpo Lake was on my map as a possible campsite so I peddled on. I set up a camp at what I thought would be a wonderful sunrise view of the lake with the high mountains of Tweedsmuir National Park to the west. As I was relaxing after a freeze dried camp stove dinner, a float plane landed on the lake, and motored up to my camp. Two fellows climbed out on the float, and threw fly lines in the water hoping for a trout dinner. We were talking about my trip when the pilot asked,

“What was I doing tomorrow?” I responded:

“More of the same! Just heading for Bella Coola.”

“Would you like to spend the day flying with us tomorrow?

I’ll bring you back in the late afternoon?”

“Yes”, I enthusiastically replied.

They motored off to the upper end of the lake to spend the night in a hunter’s cabin.

When they arrived at my camp the next morning, I had finished breakfast, packed everything, and had placed my bike inside the tent. We rose off the lake in the early morning light setting a heading of north by northeast. Flying over the land I had been so close to on the bike gave me another perspective. I wondered just where we would turn back as we buzzed small lakes, a moose, and beaver dams. We landed on Tsacha Lake. They ran the plane up on the lake bank at the MacKenzie Trail Lodge where we had trout for lunch. We talked to the owners about their future. They were convinced that the lodge would become a regular stopping point between Vancouver, British Columbia, the Yukon, and Alaska. We rolled a drum of petrol in a wheelbarrow down to the beach where we loaded up the 1942 Cessna 195 three bladed tri-tail. This was as far as my hosts from Los Angeles were going north that day, and we returned to Nimpo Lake where I prepared a solo dinner of freeze dried spaghetti.

The next morning I packed up for the long uphill climb to Tweedsmuir National Park where I had heard a Ranger could put me up, and save me a sleepless night in Grizzly country. About a half hour into the ride, I saw a plane on a northwest flight plan which was probably my Cessna friends headed for the Yukon. I returned to the task at hand with my head down while pushing in 13th of my 18 gears when I heard the sound of a plane ahead of me. When I looked up, the Cessna was coming down the road right at me at about 50 feet off the dirt. The pilot pulled up to my right while the copilot waved out the window. They then returned to their flight plan leaving me breathless from the excitement with one foot on the ground, and needing a drink. Evidently they had seen me from the northwest, and turned around to give me a thrill. I felt like Gary Grant in the movie “North by Northwest”.

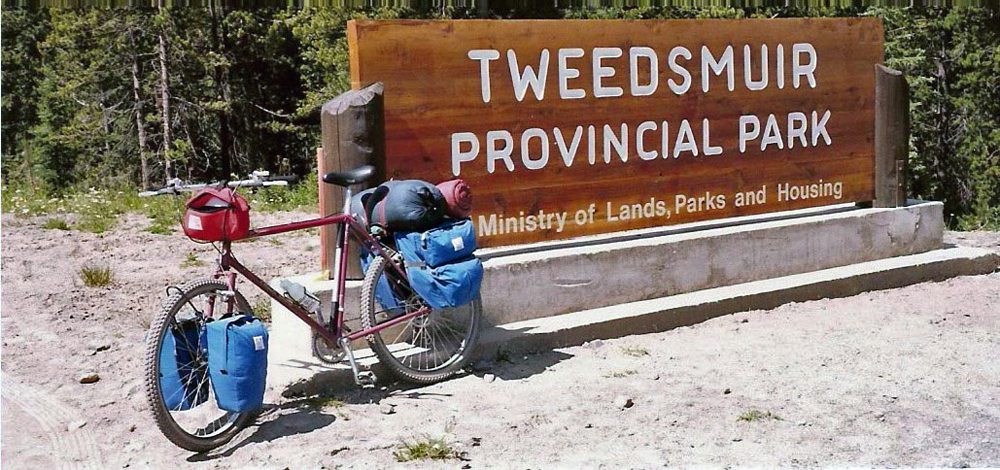

An Eye Out for Grizzlies

When I arrived at Tweedsmuir Provincial Park in the late afternoon, the Ranger was not in residence. This made me nervous as I did not want to set up a tent in what was reputedly well-traveled grizzly route. I had had bear experiences growing up in Montana, and bears just plain scare me. Because I had a lot of mid- summer northern daylight remaining, I decided to ride on toward Bella Coola. I didn’t have a topo map but I knew the road ahead was up and down, steep, long and repetitious. They even had a name for it when they were bulldozing it with a cable driven blade: “The Precipice.” I had already climbed about 1000 feet to Heckman pass at 4573 and the road would drop at 18% for about 1500 feet, climb again for about 1000 feet then drop at 18% to the Bella Coola valley at sea level. I didn’t look forward to the difficult climbs ahead but the thought of grizzlies carried me along. By the time I reached a motel on the valley floor I had 75 miles in back of me, it was late in the day, and I needed a shower, a cold drink, and a meal cooked by someone else.

The motel owner asked me clean up a campground in return for a hot meal. I jumped at the offer and when we got there we found part of the campground had been destroyed by a grizzly the previous night. Four French school teachers were huddled together on top of the table next to their tents after a night with a grizzly. The following morning I continued on to Bella Coola riding past log rafts, abandoned boat houses, road repairs. I was on a paved road again after days of dirt, and rocks. I looked back towards the mountains and wondered how high they were, and how difficult it must have been to finally bring the roads from the east, and the west together using old equipment and sturdy men on 18% grades.

A Return Via Bus

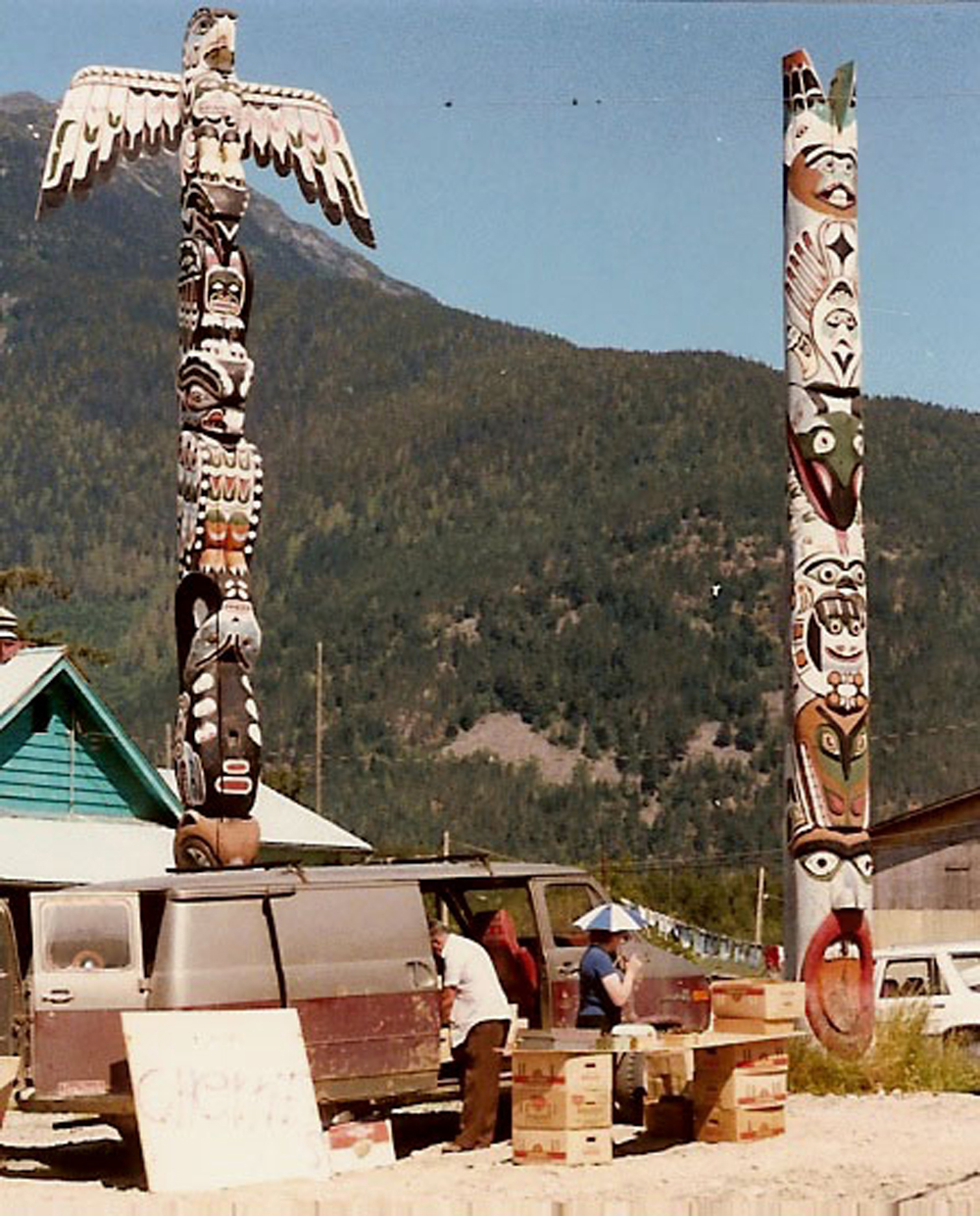

Bella Coola, with its totem poles, steep roofed church, fishing boats, adjacent hay fields, and small business center was a relief. I looked forward to a real bed, another beer, and the ride back to William’s Lake on the bus.

The following morning I stuffed my bike in the luggage compartment of the bus to the amazement of bus driver Dennis Murray. I sat back ready to retrace my week-long journey in just a few hours getting a new perspective on the road. It was hard to recognize anything on the way back while looking out the right side of a bus traveling miles an hour faster than my bike. I enjoyed the time Dennis geared down to make the grades. I don’t remember a single passenger boarding the bus for the 456 km ride back except two fellows who boarded with me in Bella Coola.

When we arrived in the afternoon at Williams Lake, I retrieved the keys to the car, and took a motel room in anticipation of the trip back to Ogden. It would take two or three days depending on what came up along the way.

The Chilcotin was a ride to remember. When I returned, I purchased the book “The Road Runs West” which describes Highway 20’s history. The book was yet another slant on a wonderful country. The characters in the books, and the stories about their lives left me wondering just what would have happened if things had gone wrong for me as I peddled what could have been extremely harsh country, nasty weather, and a complete lack of quick medical assistance.

Notes:

- The route is not that far but in 1984 there were only two stretches of pavement totaling approximately 50 of the 283 miles. The road base was rocky with stretches of gravel or graded mountain soil.

- On invitation, I spent two days traveling by float plane out of Nimpo Lake sightseeing. I stored my bike in the tent.

- I was afraid to camp at Tweedsmuir National Park because of the threat of grizzly bears so I rode from Anahim Lake to Hagensborg. A very long exhausting day.

- I spent one day cleaning up a campground at Hagensborg east of Bella Coola after a grizzly bear tore it up and frightened four people from France.

- A book titled “THE ROAD RUNS WEST” details the years of road construction by men coming east to meet the men going west.

- Bike shops in Williams Lake state that people are now riding the route one way to get to the ferries in Bella Coola.

The Bike:

According to Matt Howard owner of The Bike Shop in South Ogden, who sold me the TREK, is that the bike did not have very big tires and zero suspension to make the ride tolerable. It did not have disc brakes or front and rear suspension. It did not have the huge gear range with a low end that makes it possible to climb the steepest grades. Finally that early mountain bike was a lot heavier than today’s version.

Lived in Bella Coola between 1989 and 1993. The road was better maintained then, but pretty much unchanged. Would make a great trip today. Thanks for the memories.

I remember when you did this. I was very young, but your experience gave me years of daydreaming about going on such an adventure. Wish I had followed through on those dreams

Very impressive considering the conditions at the time. Im thinking of doing this ride as part of a circle route from Williams Lake to Port Hardy and down and over to North Vancouver.

I too am scared of bears. This is what causes hesitation in planning the trip. Will see…

Thanks for the story!

Comments are closed.