By Charles Pekow — Everything you’ll need to know – and then some– about the rail-to-trail movement can be found in a new tome. And the author, Peter Harnik, should know more about the history than anyone. He, as much as anybody, has sparked and led the cause since its beginning as a national movement and we can thank him for the many converted railroad lines we now enjoy riding – and the many more sure to come.

Harnik cofounded the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy back in 1986, the organization that initially focused exclusively on converting abandoned railroads into recreational paths. (Note: I’ve known Harnik for decades and collaborated with him on some projects years ago.)

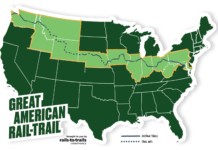

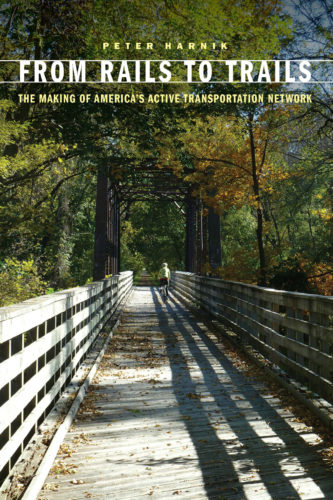

In From Rails to Trails: The Making of America’s Active Transportation Network, Harnik tells the story of the movement, describing the legislative battles in Washington to get federal funding, and many state and local fights and the coping with non-believers and reluctant railroads. The book is not difficult to read.

In From Rails to Trails: The Making of America’s Active Transportation Network, Harnik tells the story of the movement, describing the legislative battles in Washington to get federal funding, and many state and local fights and the coping with non-believers and reluctant railroads. The book is not difficult to read.

It is, however, East Coast oriented as Harnik lives on the East Coast and describes many firsthand experiences. The unfortunate part for Mountain West folks is that it’s the one region in the country that gets very little play and Harnik discusses projects closer to the nation’s capital, with examples from Pennsylvania, Ohio, New York and so on, but not much out west.

But he gives a good overview, starting with the history of railroads and how these lines that connect towns by train unwittingly became ideal corridors for new means of transit between the communities. They tended to avoid steep hills and heavy traffic crossings whenever possible and include overpasses and bridges that work just as well for bicyclists and hikers since they became available with the 20th Century decline of rail transit, caused by everything from the rise of the auto to the Great Depression.

Harnik then takes us on a history of the bicycle and how it became practical and popular, and its ups (during World War II when auto production declined) and downs (post-war when the automobile caught on). We get a detailed history of the decline of the railroad, an essential part of the story but the reader gets tired of example after example.

Once we get the needed background, Harnik gives us a history of the rail-trail, starting with the prototypes before the concept caught on; such as the Illinois Prairie Path, Stony Valley Trail in Pennsylvania and the short Cathedral Aisle in South Carolina dating as far back as 1939. Then Harnik takes on a chronology of all the legislative battles it took to get crucial federal support. We read about some unsung heroes, including congressional staff member Tom Allison who worked behind the scenes to get legislation passed. (Then again, we never hear about congressional staffers who toil anonymously in favor of their bosses who need the publicity, but that’s another matter.)

The first major federal funding for the movement came in the form of $25 million included in bigger railroad legislation, a common legislative tactic. As the book says, “there had been the 1968 National Trails System Act, but in comparison to canals, railroads, and roadways, trails had seemed laughingly unqualified for funding.”

As you’d expect, many Republicans opposed funding trails. The book sometimes gets bogged down in minutia about legislation, though.

But we learn the valuable lesson from the book on how much goes into the making of a rail-trail, even when the abandoned corridor lies there for the taking. But we learn of the victorious struggles, such as against the utility in Virginia initially reluctant to acquiesce to the Washington & Old Dominion Trail in Northern Virginia, now a well-used trail impossible to object to. (The electric company eventually saw the value.) A Baltimore County executive tried (but failed) to stop the Torrey Brown Rail Trail which runs from Cockeysville north of Baltimore to the Pennsylvania state line. Of course, the movement lost many battles, including the proposed Trail of Two Cities between Omaha and Lincoln Nebraska when other real estate interests outbid trail advocates.

And of course, many battles had to be fought in court and a chapter tells us of the significant legal decisions. Landowners wanted to expand their farms or backyards or didn’t want people running and riding past their backyard. Some cases were won; some lost. But the movement won a major victory with a ruling that a corridor used for “public travel” didn’t just mean trains. But other courts ruled that railroads could choose how to dispose of their real estate.

The book can’t be considered a “how-to”, but it does explain how Harnik’s conservancy (of which I am a charter member) built a political base. He didn’t claim to start the movement but the conservancy nationalized it, starting by looking to see what was already going on around the nation. It found trail conversion needed a triangle: “a formal plan of action, a public agency agreeing to own the facility, and an advocacy organization pushing for approval.” A chapter explains how to build a base – bicyclists alone probably won’t do it though they often spearhead the drive; add other trail users, conservationists, etc. Doing so may require compromise – cyclists and equestrians have to learn to share.

There are all sorts of ways to turn skeptics around and deal with unique situations. The book will get you thinking about these matters. When a Wisconsin farmer complained about having to move cattle across the trail, the commission in charge agreed to include a special gate – and now watching the cows cross has become an attraction for trail users. Sometimes a philanthropist will buy the real estate if no government has the cash on hand. Different government agencies use different rules. Some concern themselves mainly with transportation; others with recreation. Tunnels and bridges are needed to get from here to there but present their own set of problems with structure, safety, vandalism, etc.

From Rails to Trails takes you in historical order through the necessary preconditions and prehistory of the rail-to-trail movement, the railroad, the bicycle, etc. The book shows how the movement formed and all entities you have to fight: legislatures, courts, communities, governments, and all the places trails can be built: urban, suburbs, rural, tunnel, etc.

Most trails replaced railroad tracks with pavement, suitable for all bikes, but some trails remain gravel. By and large, trails are flat and connect communities; they’re not built for mountain biking.

If you want to start or expand a trail in your community (or between yours and another), you need to read this book. If you’re already advocating for trails, you can pick up plenty of hints on what will work. Perhaps a subsequent book on bike advocacy can include examples from the Mountain West. And anyone who reads the book will have to come away with some appreciation for how the trails they ride got there.

From Rails to Trails: The Making of America’s Active Transportation Network, 240-page paperback or e-book, $19.95, University of Nebraska Press, https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/nebraska/9781496222060/.