By Howard Shafer

The Black Hills of South Dakota are rumored to have some spectacular bicycling. Last September, we decided to see for ourselves. We planned a seven-day, self-contained tour of the area, but when we realized we didn’t have enough time, we settled for day rides from a Hill City base. “We” included myself plus my cycling partner and lifetime companion, Jacquette Ward. The 650 mile drive from Salt Lake City to Hill City, South Dakota took ten hours.

Hill City

Hill City rests in the heart of the Black Hills. It was founded as a mining town in 1876 after George Armstrong Custer discovered gold a little to the south. Today, it retains some of its mining day looks but those looks have been updated by a thriving tourist industry. Still, it remains a pretty little town of about 1000 inhabitants and includes a railroad station and museum dominated by a colorful locomotive from the late 1800s.

The Peter Norbeck Scenic Byway lies a few miles southeast of Hill City. People come from all over the world to drive this road, which includes sections of Highways SD 87, SD 89, SD 244, and US 16A. The locals ran on and on about how treacherous it would be for cyclists due to its narrow, twisting nature as well as its rubber-necking tourists, but such descriptions just made our mouths water. We could hardly wait to try it, and that’s why we found ourselves early our first morning unloading our bicycles a couple of miles south of Hill City at the junction of US 16 and SD 87. But the temperature had dipped below thirty degrees, and even after pulling on every scrap of clothing we had, we couldn’t control our shivering. Finally, we admitted defeat, piled back into our car, and returned to town.

Instead of bicycling, we browsed several arts and crafts centers and bought earrings and a horse-hair pottery jar from a Sioux artist named Tonkiaishawien Kientunkeah, who went by “Tonki.” He said his children and grandchildren were all artists and all displayed their work in his store. He also said his grandfather taught him never to blame others when things go wrong but to always take responsibility himself, because if he didn’t, he would lose control of his life. He said this philosophy saved him from the fate of many of his Indian brothers. “You can’t move ahead with your life, if you can’t get rid of your anger,” he said.

Later that morning, after the sun had warmed the air, we decided to try bicycling again but with different plans because the day was half gone. We opted to explore the closest section of the Mickelson Trail.

Mickelson Trail

The George S. Mickelson Trail runs 109 miles from the gambling glitter of Deadwood in the north to the town of Edgemont in the south. Long sections traverse wild country far from any roads. The trail includes four tunnels and more than one hundred railroad bridges, some original, others replicas of the original trestles. Important for us, it has a trailhead in Hill City. When we first planned our trip, we’d hoped to bicycle its full length, but we discovered it has a “packed gravel” surface, and we were road bikers. Road bikes don’t do well on gravel, so we rode only the fifteen miles from Hill City south to Custer. Most of our first ten miles were easy uphill. The gravel wasn’t that bad either, although without mountain bikes, we felt like our handlebars and saddles had become heavy-duty vibrators that shook our hands and rears without mercy. Worse was, especially on the downhill into Custer, that the trail sometimes morphed from its normally packed surface into deep gravel that caused our bikes to flounder. Each time we hit a patch, we were sure we’d met our doom.

The trail took us past the Native Americans’ colossal answer to Mount Rushmore’s presidents, the immense some-day statue of the Oglala Sioux’s great chief, Crazy Horse (George Armstrong Custer met him on the Little Bighorn River in south-eastern Montana), under construction on a hill directly above us. We marveled at its size, practically an entire mountain, and wondered if it would ever be completed. Eventually we arrived in the town of Custer miraculously intact in spite of the gravel. We explored the wide main street and frontier architecture of this town of 2100 inhabitants, eating lunch in front of the shop where Fly Speck Billy murdered Abe Barnes in 1881. Then it was a saloon. Now it’s a bakery.

One day later, 560 cyclists from 28 states began the fifteenth annual three-day Mickelson Trail Trek, enthusiastically bicycling the full 109 miles from Edgemont to Deadwood. We hope they were smarter than we were and were all riding mountain bikes.

Peter Norbeck Scenic Byway

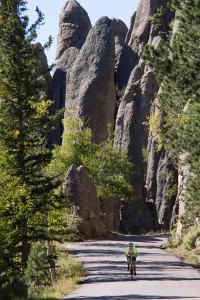

The next morning, which happened to be the day of the equinox and was fortunately much warmer, we returned to yesterday’s start and rode bravely southward, climbing SD 87 toward towering pinnacles while dreading the onslaught of the maniacal tourists we had been told to expect. But few automobiles materialized, and due to the many switchbacks, those few kept their speed down. Their drivers were almost universally considerate anyway. After six miles of moderate climbing that included many switchbacks and one nine foot wide tunnel hewn from solid rock, we entered Custer State Park, and descended twelve miles on the Needles Highway past spectacular granite spires that give the road its name. We even passed directly through two of these spires via single-lane tunnels where automobiles waited while we pedaled. We stopped to watch some rock climbers and rode alongside rushing streams surrounded by the dark forests that give this area its name. The story is that the ponderosa pine needles scatter light in such a way that the forests appear almost black from a distance. Since we started too late and took too many pictures to complete the full sixty miles in any reasonable time, we turned left onto CR 753 and shortened the ride by about fifteen miles. We had CR 753 absolutely to ourselves, sharing it only with birds and animals. Once we startled a beaver that flopped into the water near its lodge but then floated lazily in the middle of the pond and ignored us until I got out my camera. That seemed to be its signal to disappear.

After CR 753, we turned left onto US 16A known as the Iron Mountain Road, and rode a grinding, switch-backed uphill to the Norbeck Overlook. From there we saw at a distance the majesty of the four Mount Rushmore presidents. Then we coasted downhill through two more narrow tunnels and negotiated three “pigtail” loops that spiraled back over themselves.

Finally, we turned left onto SD 244 and struggled up the hill to the Mount Rushmore National Memorial where we would observe George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln up close. Someone told us this road was three miles of 18% grade. Maybe that’s an exaggeration and maybe it isn’t, but that four-lane, treeless highway climbing toward the memorial is definitely long and steep, especially with the sun high and the heat relentless. We expected to finish with a relaxing downhill back to our car, but it was not to be. The final miles rolled up and down for what seemed forever. We’d only gawked and never stopped at the memorial, and our water was almost gone. All we could do was wet our mouths a tiny bit at the top of each hill and continue. We finished dry-mouthed and tired but happy after 42 miles and 5400 feet of climbing. The pavement had been universally smooth. It had been a great day.

There were many other rides near Hill City we wanted to try, especially the ten mile grade from Hill City east to Keystone and the 40 mile Wildlife Loop Road in the south part of Custer State Park, but we had run out of time. Instead, near twilight, we drove the loop, sighting many bison and pronghorns along the way.

Spearfish Canyon Scenic Byway

About fifty miles north of Hill City, Spearfish Canyon winds through the Pahasapa limestone formation for about 15 miles from the town of Spearfish to the Cheyenne Junction way-station. White buttresses line the top of the canyon. Sparkling waterfalls cascade down from them. Pahasapa is a Sioux word and means Black Hills.

Spearfish is a delightful town with a well-preserved center filled with historic buildings. For our ride, we parked our car on South Canyon Street in a shady combination park, campground, and fish hatchery populated by many picnickers and joggers.

The first two thirds of the Spearfish Scenic Byway has well-used bike lanes. Then the road narrows and a sign warns that bicycling “is not advised.” Beyond that sign lay the most delightful part of our ride. The narrow road added to our feeling of being one with the surroundings: dark green forests, a mountain stream flowing into a quiet lake, a hushed kind of solitude, and very little traffic. A dog named Buddy followed us for a couple of miles, a year-old mixed breed pup that looked like a long-legged setter. He raced ahead, stopped to explore side roads, streams, and smells, and then loped back to us. We found his owner relaxing at Cheyenne Junction. We assumed the well-tattooed Dave was just a local hillbilly, until he told us he had retired from his law practice to play poker and had made $2.4 million in one recent year.

When lightning began flashing among the mean-looking clouds hovering over Spearfish and thunder reverberated off the canyon walls, we hurried back the way we’d come. We were back to our car before the deluge hit. That ride was 39 miles with 1200 feet of climbing.

Theodore Roosevelt National Park

Technically Roosevelt National Park, outside Medora, North Dakota, is not part of the Black Hills. But the road looping through it is perfect for cycling. It would have been a shame to miss. We stayed overnight in Medora and got an early start to avoid the automobiles, but our ride almost got cancelled. The bison did it.

We’d bicycled only a few miles when we met them crossing the road. We waited half an hour, standing patiently beside our bicycles, but the bison would not retreat. The closer they came, the more tightly I clutched my handlebars. I watched for raised tails. The ranger had told us that if the bulls lift their tails, they were ready to charge. He’d said that bison are used to cars, but they don’t understand cyclists, and we should stay at least three hundred feet away. The bison were not cooperating. “They look as harmless as lambs,” Jacquette said. “Can’t we just ride through them.”

Being basically a coward, I wouldn’t hear of it. So I thought a minute, bit my lip, and was trying to tell Jacquette we ought to turn back when two rangers showed up in a pickup truck and rescued us.

We got to bicycle beside (and I hoped, protected by) an official National Park pickup, that nudged one cow and her calf out of our path, and kept the bulls all on the far side of the truck.

We’d already encountered bison that day, and before it was over, we’d encounter more. According to Jacquette, I came within twenty feet of a big bull on a downhill and didn’t even see him. She herself made eye contact. She stared at him, and he stared at her, but he wasn’t interested. Later we had to weave through a row of parked vehicles full of gawking tourists to get past a second herd.

We recommend this short ride (38 miles with 2800 feet of climbing) if you’re ever near Theodore Roosevelt National Park. Start in Medora (population: a few more than one hundred residents). This town was founded in 1883 as a meat packing plant that shipped refrigerated beef to cities in the East. It is an interesting and picturesque little town with several motels and campgrounds due to its access to a national park named after the president of the United States who once had a ranch there. The roads through the park are good, and we encountered little traffic. The Little Missouri River meanders through the park surrounded gray bluffs streaked with pastel colors, clay domes, twisted pinnacles, groves of trees, rolling hills, grassy meadows occupied with prairie dogs standing like surveyors’ stakes, and herds of bison, wild horses, and elk.

spectacular cycling.

We climbed a lot of hills, but none was terribly long. From their crests we saw other hills, domes, and prairie receding away from us in all directions.

We made our rides under cool autumn skies. Whether it’s the Black Hills or Theodore Roosevelt National Park, we believe the best times to go are in the fall, when the leaves change color, or in the spring with its extravagance of wild flowers. We believe you’ll want to avoid the cold and drifting snows of winter as well as the blazing heat of summer. But you’ll love the cycling. If you get the chance, take advantage of the opportunity. You’ll be glad you did.

For more information:

http://www.mickelsontrailaffiliates.com/

http://gfp.sd.gov/state-parks/directory/mickelson-trail/

http://www.spearfish.com/canyon/

http://www.blackhillsbadlands.com/home/planyourtrip/maps

http://www.theblackhills.com