By Erik Moen, PT — Heel pain is not all that common to bicycling. The most frequent source of heel pain originates from excessive strain in pedaling. Bicycling is obviously a highly cyclical sport. A two hour ride has about 10800 crank revolutions if you average 90 revolutions per minute (rpm). The prevalence of heel pain is mostly related to the calf and secondary to the foot. The primary role of the calf and the foot in pedaling is to create a rigid lever to the pedal so as to transfer force from the quadriceps and gluteals into torque to the drive train. Bicycling-related heel pain can be a significant detractor from bicycling.

The most common source of heel pain for the bicyclist is a strain of the Achilles tendon at its bony attachment to the calcaneus or heel bone. This type of irritation is sometimes called an apophysitis. This strain is simply mild tearing of the tendinous insertion to the bone. This causes inflammation (swelling, redness, pain, and sometimes heat). It will have obvious tenderness with touching the area and when the Achilles tendon is loaded by weight, such as standing on toes.

Plantar fasciitis is a source of heel pain but is often times not directly caused by bicycling. The plantar fascia is connective tissue that passively supports the bottom of the foot in stance and during activity. Plantar fascia can become strained, much like that of the tendon insertion to a bone. Plantar fasciitis is an irritation of the plantar fascia’s attachment at the medial tubercle of the calcaneus (heel bone). It is often times initiated by walking and/or running. It is usually a result of irregular motion of the foot, weakness of the calf, or inflexibility of the calf. Concurrent plantar fasciitis can be aggravated by bicycling if you are using a soft shoe or are placing the foot particularly back on the pedal, or the cleat being too far forward on the shoe.

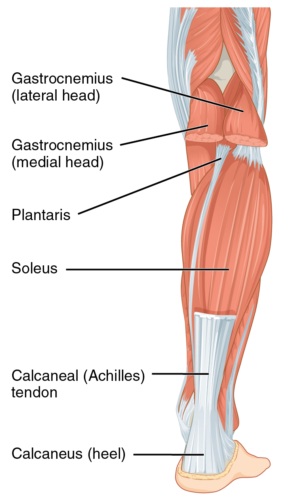

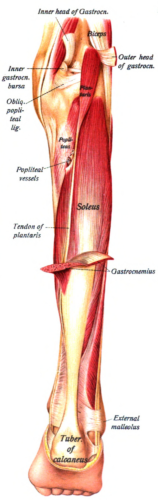

The calf musculature (gastrocnemius and soleus) attach at the back of the knee and run down the lower leg (tibia and fibula) and have a common blending into what is called the Achilles tendon. The Achilles tendon attaches to the back of the heel bone, or calcaneus. The calf/Achilles is stretched by dorsi-flexing the foot or bringing toes/foot up towards your shin. When the calf musculature contracts or shortens it pushes the foot down into a plantar-flexed position.

Actions of the calf musculature are numerous. The calf creates motions (think gas pedal), attenuates load (return from jump), creates leverage for the foot (pedal a bike), and helps stabilize the foot for balance. The calf musculature is commonly known as a plantar flexor. The calf is used in bicycling mostly as a means of keeping the foot rigid during the propulsive phase of bicycling (push from the quadriceps and gluteals). Actual ankle range of motion in bicycling is somewhat limited. It is typically about 20 degrees in a plantar flexed (toe down) bias when pedaling at 90rpm. In fact, the foot does not assume any dorsiflexion in pedaling normal cadences on a well fit bicycle. Normal ankle range of motion for a person walking and running should be near 40 degrees when assessed from a standing calf stretch. Typical plantar flexion range of motion is 70 – 80 degrees. This makes an approximate 110 degree arc for normal motion of the foot and ankle. Hardly the motion required of typical endurance bicycling.

Common origins of bicycling related heel pain can come from training errors, poor equipment and equipment positioning and irregular pedaling. Training errors are frequently a result of too much, too soon. The common denominators of training are volume and intensity. Excessive loading as a result of quick acceleration of either volume or intensity loads can generate heel pain. Equipment issues are most often times related to the excessive forward positioning of a cleat on a shoe. This creates a long lever of the foot to the pedal, thus increasing the demand on the calf to oppose the extension moment in pedaling from the quad/glut. Good cleat placement allows for you to take advantage of nature bony levers of the foot to better withstand the pedaling force transference through the foot. Other common equipment irregularities are saddles that are excessively low or high. Low saddles can create an excessive eccentric (lengthening phase) load to calf, where high saddles can over strain a calf from end range concentric contractions (shortening phase). Irregular pedaling mechanics or skills can be a source of heel pain. The use of large gears and low cadence can directly lead to an overstrain of the Achilles tendon.

Treatment is, as always, a function of the pathomechanics or source of the injury. Low cadence pedaling style?…try increasing your cadence. Forward cleat?…move it back. Poor calf strength relative to your training?…work on strength. The trick is finding the true issue or issues related to your problem. Acute (fresh) pain should be managed with the use of ice.

Good pedaling, attention to proper training and bike positioning will help you avoid heel pain related to bicycling. Bicycling does not do much for calf flexibility. Endurance road bicycling requires very little calf flexibility. Calf flexibility should be attended to so as to tolerate activities that we deem as healthy and necessary, such as walking or running. Work it out!

Erik Moen PT is a Physical Therapist at Corpore Sano PT (www.CorporeSanoPT.com). Corpore Sano specializes in treatment, bicycle retrofit and management of the injured bicyclist.