By Loren Hettinger — I had thought about the ride again, wondering with my cousin, Tom, in February if we could do enough training to hone the old bodies into something resembling our former selves. But COVID-19 put an end to any plans—perhaps mercifully. I dug out a report that I had written about the tour we had done in 2011. In reading the account, it seemed quite fun . . . of course the climbs were long and sometimes really steep, but not that bad . . . were they? . . . I read through the account in more detail:

The Kokopelli symbol guides travelers along a trail of ~ 140 miles between Fruita (Loma actually) and Moab. The dancing flautist image is now common throughout the southwest, generally embodying carefree and joyous adventure. However, Kokopelli’s Native American origin has other meanings such as a fertility deity, and among Hopi, a humped-up carrier of unborn children for distribution–and feared by young girls and possibly any unmarried male or female. Another aspect is that Kokopelli’s flute playing chases away winter, bringing spring, or in Zuni culture, is associated with rains. I think most of us at the trailhead in Loma, CO in 2011 for this trip latched onto the carefree, rock skipping, joyous caricature, hoping no surprising news of children or rain storms interrupted our mountain-biking journey.

After meeting the organizers, guides, and other riders at the trailhead–and in gazing at the daunting first climb up the ridge of Mary’s Loop, we carefully did a last lube of the chain, and topped-off our water bottles and Camelbacks. I did a final check, making sure that support items, such as spare clothes, extra gloves, sleeping bag and a tent (and maybe a few bottles of beer) had been placed into the World-Wide River outfitter’s trailer, which would meet us for a lunch stop and then at a camp site at the end of each day.

This trip was headlined as the Tour de Bloom by the COPMOBA trail advocacy group; a worthy cause to maintain existing trails and construct new ones in the western Colorado and eastern Utah area. And by being scheduled in mid-May, the ride was aptly named, as there were flashes of brilliance among the hills—paintbrush, scarlet claret-cup cacti, scarlet globemallow, the beautifully ornate sego lily or mariposa, and indigo-blue larkspur.

There were 30 of us on this trip, mostly seasoned mountain bikers, led by five younger, hard-body guys—quite lean I had observed the first day–who often disappeared into the distance, but with the ability to circle back to keep track of the “herd.”

On this, the second day of the trip, I scouted a premium campsite in the Cowskin Campground. This site is situated in a partial amphitheater of Navajo Sandstone, and is protected from the winds in Rabbit Valley that had bedeviled us with occasional small dust devils and sandblasts a day earlier–and an interesting coalminer visage of dirt on sunblock.

I spied a nearly level site for my tent near the cliffs in the shade of a juniper tree and then waited in a long line for the hand-pumped portable showers, drying with a long-sleeved undershirt, the price of forgetting a towel. This “towel” was left to dry, impaled on several branches of antelope bitterbrush. I climbed into the tent soon after dinner of fajitas, chips and salsa, all washed down with a tasty beer (yeah, all relatively plush), as the next day was to be a long jaunt of ~ 30 miles and 6,000 feet of climbing.

In addition to protection from the wind, an added feature of this campsite was the acoustics provided by the amphitheater-like cliffs; I could hear patches of conversation from those still around the campfire. Sometime during the night or perhaps the wee hours of the morning, I slipped on my running shoes to protect my feet from prickly pear and shuffled out from the tent for a much-needed pee. I gazed into the sky, hoping for a view of the constellations, the Milky Way. The tranquility of the night with the bright, seemingly close stars was profound, and I stood transfixed staring skyward while watering a clump of grass. My reverie was abruptly shattered by . . . how do I describe this tactfully . . . a loud, resonating, flatulent explosion–as if a huge rock had been thrown into the middle of my serene contemplation of the sky. This from a tent farther along the small wash that angled across the site. The sound was amplified as it echoed off the sandstone walls. I was quite amazed by this achievement, saying to myself, “Wow!” and hoped I could identify the creator of such an acoustical masterpiece. I wasn’t sure exactly from which tent the sound had emanated. The episode though reminded me of an old joke, of a prospector in the early days who would yell out across the wide canyons and rocky towers, “Get outta bed,” upon retiring and have the echo come back in the morning as his alarm clock.

In the morning, we gathered around the outfitter’s cooking area and “kitchen,” this in response to the aroma of frying bacon, and waited for the full monte, holding steaming mugs of cowboy coffee. Breakfast wasn’t a time to dally though, and after hustling my baggage into the outfitter’s trailer, I stuck several Honey Stinger and Hammer Gel packs into a jersey pocket and a large water bottle of mix into a cage, ready for a long morning.

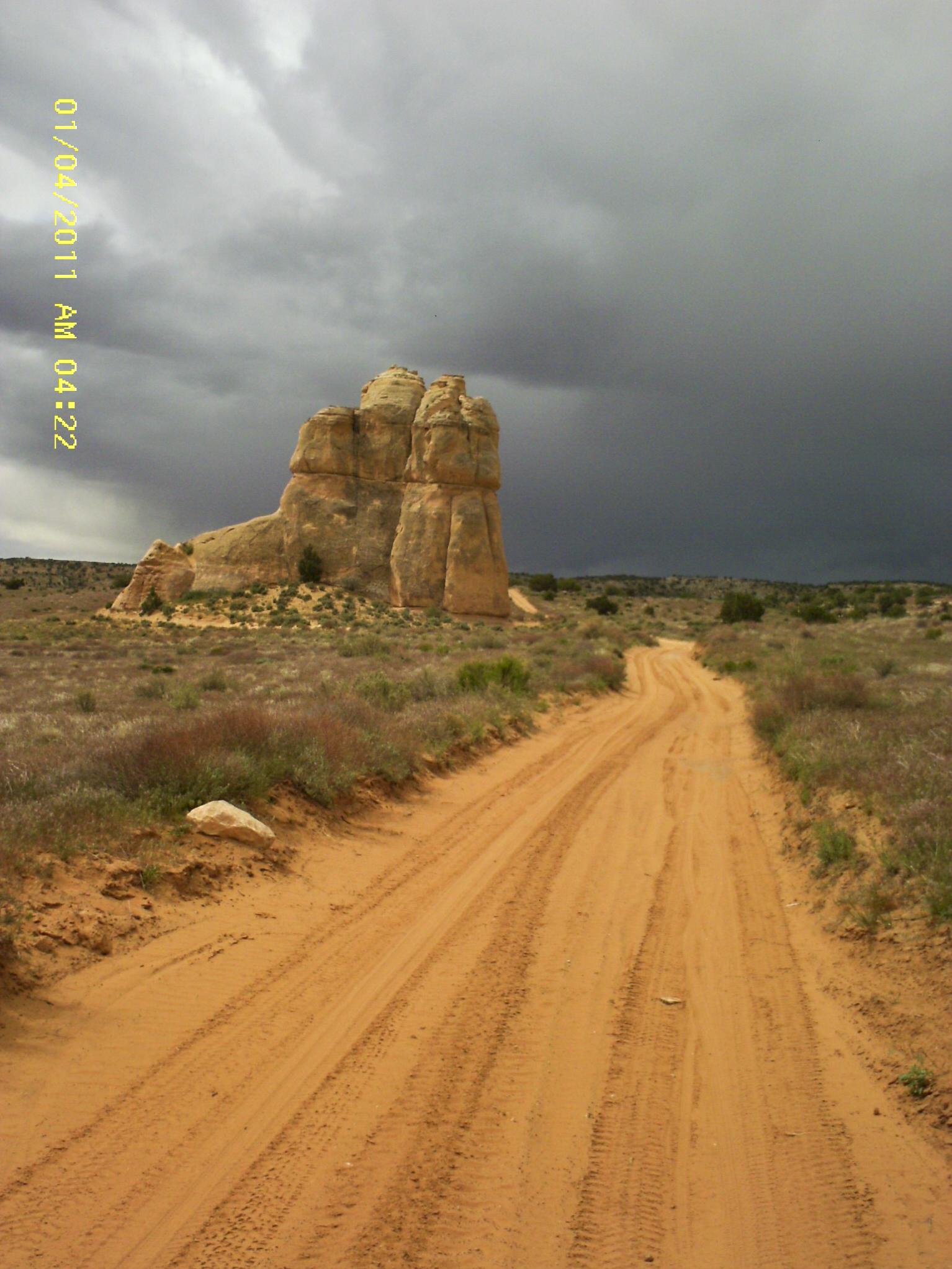

The trail from the camp quickly transcended into a steep climb, and I tried to settle into a rhythm, but soon noticed a strong taste of pancakes, hoping breakfast stayed where it was. The climb continued into Cottonwood Canyon, including a long section of rocky–or more appropriate bouldery–hike-a-bike and veered from the Top-o-the-World Trail. From this apex, the track then steeply descended via a series of drops over broken rock; a track that has seen its share of four-wheeling activity, evidenced by frequent tire scuff marks. Everyone seemed to take the series of drops in stride, although some of the younger guys and the guides seemed to revel in this terrain, taking bigger risks.

A second climb took us to Big Cottonwood Canyon and a broad, scenic vista across red towers, buttes, and intervening deep canyons. This climb was a long-haul, first on a relatively smooth, sandy trail, but this quickly devolved into more rocky, double track. In riding up a series of ledges, the rear tire of my bike slipped out, and I suddenly performed a sort-of horizontal pommel-horse maneuver in response to a new combination of gravitational and centrifugal forces, landing on the upright end of the handlebar with my abdomen. As I was pirouetting around the bike in pain, I was aware of some luck–the one-point landing had missed an even-more sensitive area. After catching my breath, I tugged the front of my shorts outward to check the damage–a circular, purplish tattoo-like bruise had already formed. Thank God my appendix was no longer part of the picture or it may have been plucked out–a sort of grisly trophy of technical ineptitude—as the location was close.

We fled the climb in a fast descent on the Cottonwood Canyon Trail, first in a very technical, beyond-category descent called the “Rose Garden” (but with raspberries the likely reward of a mistake) and then a swooping and nicely carved single-track and to the Fisher Valley-Onion Creek Road for a lunch stop. By now, my crotch was feeling a seemingly inverse relationship of thinning chamois and conversely swelling seams, and I thought about changing, thinking this, along with a sore abdomen, might portend a long afternoon. I had a vision that the current pair of shorts had been baseball-stitched with wire, and made sure to again amply smear Chamois Butt’r onto tender places—this somewhat discreetly to avoid any smirks. At the same time, I had another look at the circular bruise to make sure nothing was bulging. It didn’t feel great, but my abdomen looked intact. The mark consisted of an imperfect circle with a short scrape leading to it, as if I had been tagged with a hot iron and perhaps part of some Bar-O ranch remuda.

The afternoon consisted of another approximately 3,000 feet of climbing alongside the Fisher Valley on the Thompson Canyon Trail, mostly on ledgey double-track or Jeep road. The climb was long and steady, so most of us took a break at the Hideout Canyon viewpoint and posed for photos. The abyss into the valley here was vertigo-inducing with drops of approximately 1,000 feet, to be offset by vertical canyon walls and several tall, narrow iron-red towers, as if part of some long-ago forgotten Medieval castle.

We continued climbing and the trail became smoother. Riding time (wheels moving) by now was over five hours. I suddenly had the out-of-gas feeling, so after thinking about the empty tank for maybe a mile, stopped and sat on the side of the double-track, sucking on energy gels. One of the guides (Rus) stopped to see what was up and noted the campsite was only about a mile farther up the road.

The North Beaver Mesa campsite is at 8,200 feet and on the shoulder of the La Sal Mountains. We had started out in the high-desert canyon landscape of sagebrush-saltbush scrub at approximately 4,500 feet, but now had ascended to the Montane Zone of ponderosa pine and Douglas-fir. This was our last night on the trail, and the group gathered after dinner around a campfire for a few beers, toasting our accomplishment and trail-forged companionship. It didn’t take long though for the cool of the evening to descend, and I wished I had thicker down in my jacket. Another day and we would complete the journey, descending to the Sand Flats Road or the Porcupine Rim Trail, depending on technical preference, respectively, and then onto Moab.

During the night, the elevation put its stamp on our journey, and early in the morning I could feel lumps of precipitation hitting the tent. I poked my head out the zippered door to a frosty scene; several inches of snow were already on the ground. I noticed my shirt towel frozen quite stiffly, crucifix-like, onto a gooseberry bush. I pulled the zippered door of the tent shut and thought about sliding back into my sleeping bag, but instead pawed through my duffle bag for a long-sleeved jersey, tights, and thick gloves.

It took a while for all of us to gather around the fire of the “kitchen” for much needed coffee. Then secondly, to figure out the clothing ensemble for the day, and hoping some of the snow would melt. We finally descended from this high-point on greasy, splashy gravel roads. At the junction to the single-track we avoided a destructive mud-fest by bailing out onto roads connecting to blacktop that parallels the Colorado River and then back on the highway to Moab.

Riding the roads and highways back to town increased the distance and delayed the time of our arrival. We jettisoned a scheduled shower after linking up with the outfitters to grab fresh clothes. Most of us (at least the guys) changed by crouching down—or some not so much—behind a retaining wall placed to protect the town from Mill Creek floods, not realizing that the view from the opposite side was unimpeded for tourists walking along a path. Bare asses and torsos seemed strikingly white in the afternoon sun compared to the rest of the ride-exposed flesh. By-passing showers was to keep a reservation at Zak’s Pizza and Beer. I mean . . . it’s all new sweat anyway . . . isn’t it? Well, maybe not so new to some of us as we closely packed ourselves into the van for the ride back to Fruita.

If the skipping, flute-playing Kokopelli symbolizes adventure in this area of canyons, rim-rock, desert-like sand, and towers, we were well served, and the trail is appropriately named. Maybe we joyously skipped among the rocks a little somewhere along the way like Kokopelli, if only in our minds. Bar-O brand aside, selective memory had me wanting to go again.