Every great adventure begins with a map.

I was sprawled out on my living room floor. Unfolded around me were three different maps of the Moab desert, La Sal mountains, and Colorado Plateau. On the screen of my nearby laptop was a fourth, a digital topographic map of the same areas. I was writing notes on a scrap of paper about possible road combinations–deciphering elevation profiles, looking for possible water sources, and making unsubstantiated guesses about the quality of the roads and trails.

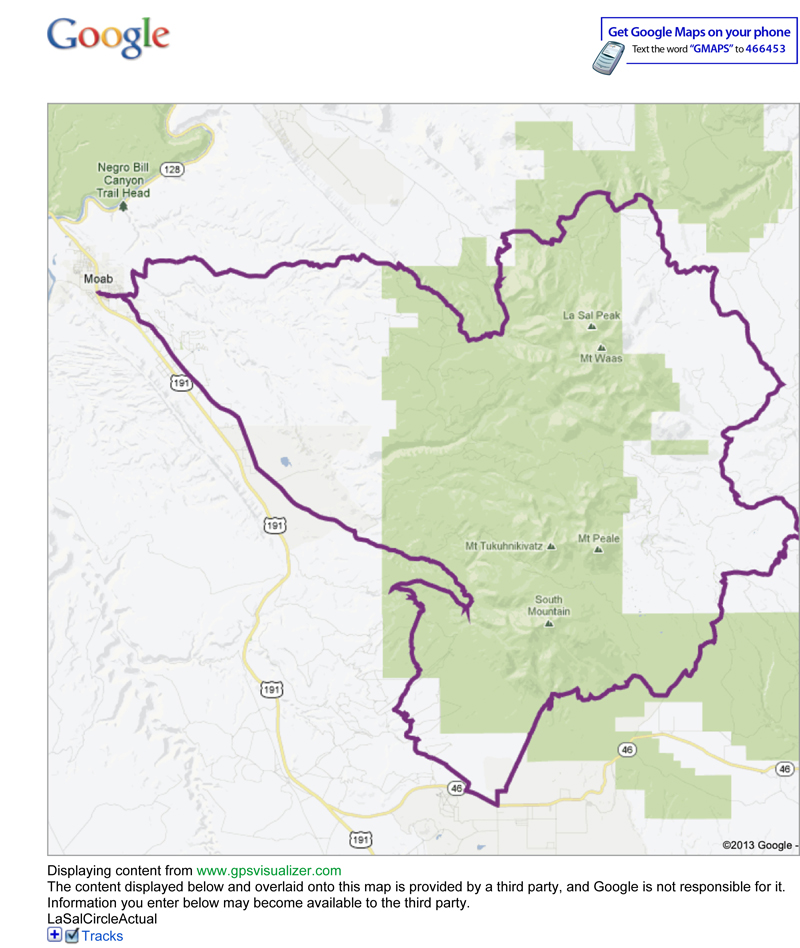

The objective, and the reason for the map-scouring and route-planning, was to spend two days riding a circle around the La Sal mountains. Could it be done? Geographically, yes. But physically? I’d have to do some pedaling to find out the answer to that question.

I continued to pour over the maps. Dirt roads dead-ended in box canyons, on mesa tops, and at the bottom of cliffs. A few connected with others, which looked promising, until they too terminated abruptly. But a few others did intersect with others still, until at last, a circle started to emerge.

On paper, the different route possibilities were legion. Lines, some solid, others dotted, criss-crossed the map arbitrarily and indiscriminately. Where many roads ended, many did not. Utah is, after all, a labyrinth of old mining, jeep, and forest roads. But which ones, if any, were rideable roads? Which ones were maintained? How many were covered in loose baby-head boulders? Would mud or snow be a hinderment? And did the Carpenter Basin Trail, clearly marked on the map, even still exist?

Sometimes maps can invoke more questions than they can answer.

I searched for information on the Internet, hoping to glean even a little bit of visual evidence about the conditions, scenery, and terrain. My searches mostly turned up empty. And that wasn’t entirely surprising. The La Sal mountains, and the world around them, are empty and vast. Some of the old roads are well traveled. But most of them seldom see any significant traffic.

After a couple of hours staring at the topographical reliefs, making notes, and drawing lines on the digital map, I felt like I had a reasonable route put together; starting and finishing in Moab, the line drawn on the map stretched just over 100 miles and climbed almost 13,000 vertical feet over forest roads, double-track, and maybe even a little bit of singletrack.

I passed along the circle to Ty Hopkins, my ride partner. “Yeah, looks fine. Should be fun.” He was right. It was a good circle. And it rounded some fantastic mountains.

I packed up the maps, and everything else I needed for the ride–8,000 calories, 4 liters of water and a UV purifier, a sleep system, bike tools, and other various necessities–and set out to circle the La Sals. The questions sparked by the map were going to be answered on the ground, one pedal revolution at a time.

I’ve always loved maps. A map is a lot more than a representation of terrain, distance, and topography. And it’s a lot more than a guide. A map is a possibility, and potential. Every road and trail, elevation contour, relief and landmark is an opportunity for adventure and discovery. A map is a mystery with but one solution: on-the-ground exploration.

Maps conjure expectation and possibility. They spark energy, and an eager exploratory ambition that flows through the heart and mind. Learning the myriad ways that trails connect, roads intersect, and mountains and valleys become one or the other is invigorating and exciting. And having a map with a well-researched circle drawn on it only compounds those feelings.

And so, it was with great excitement that Ty and I set out on another map-inspired adventure. “Time to make the donuts,” he said, as we pedaled into the unknown.

The wind was blowing from the south, into our faces. We pedaled through the outskirts of Moab, Utah, along the chip-sealed Spanish Valley Road. Cars whizzed past us in the summer sun. The nearby pastures and fields were already turning yellow. It was only May, but summertime had long displaced spring in this desert.

We rode past old trailer parks, farm houses, and junkyards. There was a disconnect between the natural beauty around us, and the crumbled, neglected housing it surrounded. Carcasses of old cars, rotting barns, and unidentified junk littered the corners of yards and fields. Dilapidated fences separated property lines. If a home had a lawn, it was dry and brown. Paint was peeling off of old siding, doors, and mailboxes, in thick, dry chips.

We followed the pink line that I drew on the map and had transferred to my GPS, now conveniently mounted to my handlebars. The line led upward. Away from town, away from the junk, and away from the encroaching summer heat. Slowly, the valley fell away as we climbed through the tawny tablelands and scrub oak. Red cliffs and sandstone domes became visible to the west. On the horizon behind us, Arches and Canyonlands National Parks were crowded with tourists. Beyond, the canyon country unfolded into a haze of time and space.

Juniper trees displaced the sagebrush and scrub oak. A rocky double track that lacked switchbacks or subtlety began where the pavement had ended. It went up. Straight up. We would soon learn that the west side of the La Sals are striped with roads just like this one.

But our spirits were high, and so were our energy levels. We happily struggled over the loose rocks and up the steep grade. We knew, or rather, we hoped, that we would soon be riding flowing mountain singletrack through patches of aspen shade. After all, the trail we were looking for was clearly marked on the map.

Originally named by Spanish explorers Sierra La Sal, or The Salt Mountains, the La Sals are laccoliths, formed through volcanic intrusions that pushed the sediment upward, forming domes and peaks. The La Sals are capped by abrupt, bald peaks that reach over 12,000 feet above sea level. Flanking the peaks is a defined timberline where the forest stops suddenly. Scree fields of shale, boulders, and year-round snow fields top the rounded summits.

The mountains are a dramatic contrast and backdrop to the canyon country that erodes away at the foot of the range. The red sandstone of Arches is offset beautifully by white snowy peaks, green pine and aspen groves, and a vertical incongruity that only the Rocky Mountains can provide. The Moab area is, as Edward Abbey claimed, “the most beautiful place on Earth.”

As early as the 1500s, Spanish explorers and traders were traveling through Sierra La Sals. The mountains were a part of what is called today the Old Spanish Trail, a rigorous, rugged trade route that connected Santa Fe, New Mexico and Los Angeles, California. John C. Fremont and Kit Carson followed the route in 1844, and upon learning that the Spanish had been using the network of trails for centuries, gave the trail its present-day name. Pack trains of horses and mules would carry hand-woven goods to California, where they’d be traded for the same horses and mules used to carry the cargo back and forth across the route.

As Ty and I pedaled, however, none of that history was on our minds. Our own exploration of the mountains, difficult in its own pneumatically enhanced manner, was starting to get rocky.

After riding through the windy and barren Spanish Valley, and climbing 2,000 feet through the boxed canyons of the La Sal foothills on loose, stony roads, we had finally arrived at where the Carpenter Basin Trail was supposed to begin. But there was no trail. We wandered around, looking for any sign of the singletrack. We found nothing. From our perch on the ridge, however, we could see dirt roads meandering below, in the direction that we ultimately needed to go. We abandoned the Carpenter Basin route, and improvised.

I was glad that I had brought the paper map. It, more than the GPS, guided us through the re-route. Eventually, we found our way back to where we had planned to go. But we lost several hundred feet of elevation in the process, and had to climb another no-switchback, no-mercy road. By the time we reached the top of that road, we were tired and hungry. “Time to stop. I need to eat,” Ty announced. I agreed.

The shadows were growing longer. The dull ache in our legs had migrated to our backs, shoulders, and wrists. We were thirsty, and out of water. Far below, Highway 46 snaked into the distant horizon, and into Colorado, where it became Highway 90. We ate a modest dinner while we watched the sun splash warm light onto the warm rocks of Canyonlands. The Abajo mountains to the south were a deep blue. The peaks behind us caught the afternoon light eagerly.

Doubt crept into our hearts. Why were we here? To prepare for the Colorado Trail Race, of course. But really, why were we here? That is, why had we each goaded the other into committing to do something like the Colorado Trail Race? If just a few hours of navigational frustration were taking such a toll, what sort of physical and emotional havoc would several days of difficulty incur? I forced food into my mouth, and swallowed it into a deep pit of despair.

There was nothing for it. And so we continued, uncertain of what the next bend would uncover, and increasingly worried about where, and when, we’d find water. “Time to make the donuts.”

Finding water didn’t take long. We heard it before we saw it. A running stream is always a wonderful sound. It’s musical, happy, and comforting. A stream doesn’t roar intimidatingly and dangerously like a river. And it doesn’t sit silent and stagnant like a pond. Instead, it trickles with an inviting melody.

The spring water was icy cold, and crystal clear. We filled our plastic bladders, our bellies, and washed our dust-crusted faces. The road turned mellow, and the riding became faster. The sunlight was golden, and for a few minutes, the world was perfect. The desert surrendered to the mountains, and suddenly we were riding through twinkling aspen groves and fir trees. We spun happily and joyfully. We had forgotten about the heat, the thirst, and the fear that had clouded our minds only minutes earlier.

The Colorado Trail race no longer seemed quite so impossible. Our enthusiasm for that adventure, and for this one, returned in a rush of natural wonder. We were sieged by beauty.

Mount Peale, the tallest of the La Sal range, was shrouded in shadow. Its snowy slopes were faded blue in the waning light. The vast approach to the steep slopes was covered in thick trees and open meadows. The moon rose in the west, round and bright. A pale light flooded the plain. “The most beautiful place on Earth”.

We made camp in a small meadow, built a fire, and ended the first day of our ride with a kingly meal of homemade rice cakes, beef jerky, and blueberry licorice.

There are easier ways to explore the wilderness. Motors for example–trucks, all-terrain-vehicles, motorbikes. There are even easier ways than motors too–the Internet, television, books. But the mountains and the deserts were not created to be easily experienced. They are not tame, forgiving places. Instead, they demand respect, intelligence, and reverence. And the best way to meet those demands is human powered. It’s too easy to forget the remote and terraced nature of nature while speeding effortlessly along a graded or paved road. Laborious and slow progress, along with blood, sweat, and tears, can create understanding, respect, and even joy.

Maybe that’s why so many mountain bike riders are trying to do things that the rest of the world says are stupid, crazy, or ridiculous. There has to be something more than physical accomplishment to riding a bike from Canada to Mexico, or from Durango to Denver. Something intangible is motivating this small but powerful ultra-racing movement. Maybe it’s the connection, and the understanding that accompanies the physical effort that is pushing more people beyond the established boundaries of sport.

Our technology is far superior than anything the Spanish traders, or Fremont ever used. But despite the lightweight bikes, the GPS computers, the water purifiers, the laser-accurate maps, and the other high-tech gear that we use today, the mountains and deserts are still difficult and dangerous places. Our reasons for traveling through them are different as well. But the pain and the fear is similar, if not identical, to what all men, in every age, have had to overcome in our efforts to move through inhospitable terrain. Those feelings of inadequacy connect us to Domiguez, Escalante, Fremont, Carson, and Powell. Our travels help us slowly understand, just as they did, the intimacies of the wilds.

A group of motorbikes sped by us. Ty and I were half way up La Sal Loop Road, with about 1200 feet behind us, and another 1200 to go. Below us, Castle Valley was distant and quiet. The small cluster of homes looked far away, and empty. The green grass in the front yards looked neon, compared to the brown and gray of the desert floor. Castleton Tower split the blue sky. North Beaver Mesa cast a long shadow over the valley. We could hear the engines of the motor bikes long after they had gone out of sight.

We both slept fitfully during the night. The moon was too bright, our bodies, too tired. And the bivvies, a little too cramped. Every hour a dog howled at the moon like a lunatic. The bellowing echoed through the still mountain valley. When dawn finally rose through the night, we broke camp, loaded our bikes, and set out once again. “Time to make the donuts.”

The morning was beautiful, and the scenery, too. We pedaled happily. Indeed, we were still happy, mostly, as we climbed the long twisted Loop Road. At last we topped out, and left behind the pavement for more dirt, dirt that tilted almost entirely downhill, all the way back to Moab. When we finally did arrive back where we had begun, only 24 hours had elapsed. But it felt like a lot more time than that had passed. We felt like strangers in a strange land.

But those foreign feelings soon conceded to the familiar rhythms of modern life–hot showers, hot food, cold milkshakes, and a fast car on a smooth highway.

When I returned home I unpacked my gear. As I did so, the feelings of uneasy excitement returned. “Can I really ride the 520 miles from Durango to Denver?” I pushed the thought away. Of course I can. One day at a time. One hour. One pedal. Just like riding a circle around the La Sal mountains.

The next day I pulled out a map of the Wasatch trails and spread it out on my floor, a notepad and my laptop nearby. “Now, where to next?”