By Joe Kurmaskie —

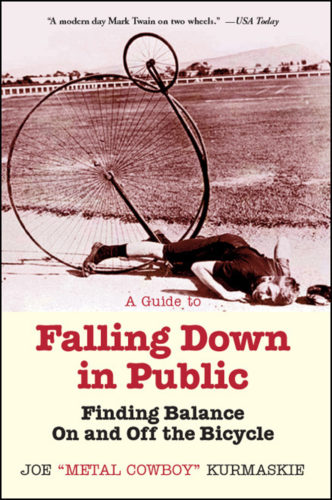

Excerpt from A Guide To Falling Down In Public

I’m learning to fly, but I ain’t got wings. Coming down is the hardest thing. —Tom Petty

During the spring of 1987, through a general lack of planning and letting life blow me around like a dandelion seed, I found myself running a bike and canoe touring company north of Gainesville, Florida, in the hamlet of White Springs.

Looking back, it was one of the most unfettered times in my life.

What wasn’t to like about White Springs? A place that time had passed over. The kudzu fought with the Spanish moss for dominance and everyone else was happy to abide. I encountered no stoplights, signs or impediments of any kind to my forward progress on bicycle, except the occasional family of mule deer, which appeared to intentionally hide in waiting for me as if it were a game. I’d pedal along at full steam only to find deer darting and dashing in front of the bicycle. It became a test of my abilities to weave and dodge and remain upright any hour of the day. I rather enjoyed it. I also enjoyed rent-free living in an ancient, rambling old plantation-style home falling down in all the right places. In the South, as long as the porch is still intact they tend to wave away those pesky structural engineers and carpetbagging renovators. If that doesn’t stop ’em, there’s dogs out back or a shotgun just inside the screen door.

I lived there by the kindness of my bike touring company partner in grime, Nancy. We’d started sleeping together almost immediately. She was ten years older than me, which made her all of thirty- one. Our running joke was I called her Mrs. Robinson in private, Nancy in public, and she called me Sid all the time . . . these versions of Sid and Nancy were far removed from the reality of the actual star-crossed rock-’n’-roll lovers, in both lifestyle choices and how it ended so badly (death and murder charges) for them. But we thought it was a bit of cheeky fun. In many ways that year was unplanned Utopia, so it couldn’t last. Sometimes to speak about your life as it’s happening is to bring it crashing down around you.

So we kept our mouths shut and cooked elaborate meals that featured collard greens, tabouli salads, and fried catfish. We put in three to four hundred miles of road work a week, leading groups on bike up backwoods bayous where the cypress knees hold court, then down the thinnest, most alluring rebel roads in northern Florida. We’d paddle up peaceful, spring-fed rivers the rest of the time.

Gainesville lay thirty miles to the south. The way its college radio station announced the release of U2’s new album, Joshua Tree, that morning, was by playing it in its entirety. I reclined the touring van’s seat and grooved to it while waiting for Nancy to paddle up with the group. We’d agreed on a pullout spot in Micanopy. I spied a no-name roadhouse bar tucked in the woods framed by Spanish moss and live oaks so thick you might have missed the place. A sign out front for Shiner Bock beer and cooked shrimp was nearly covered by kudzu.

I looked at the time, made a decision, left the van, tied the laces of each shoe to the other and put them around my neck. Then I swam, head up, across the river.

I shook off the river like a shaggy dog does to bathwater, stood in the sun a few moments, then stepped up to claim my prize. When I eased into the darkness I could hear the AC working overtime and feel peanut shells crushing underfoot against the dirt floor. Hot damn.

A glorified homestead with iced beer and spiced-up seafood gumbo, perhaps some live music on the weekends. I walked up to the bar and noted, out of the corner of my eye, a swamp rat of a guy with matted blond hair, wearing the hell out of an army jacket bastardized with nonstandard emblems. Jeans, boots, drinking a Shiner Bock at 11 a.m. on a Tuesday. A man who knew something about living in the moment.

“I’ll have one of those.” I pointed at swamp rat’s beverage of choice, and that’s when it hit me. That was Tom feckin’ Petty leaning against the bar with his sweaty, contorted cowboy hat pulled low, drinking a beer from Texas. Born and raised in Micanopy, Petty had come back home. The Gainesville radio station DJ had just been talking about the killer show he’d thrown down on the U of F campus to end a long concert tour.

He was off the clock and the map. Hanging in a place that probably made him feel fifteen again. A place where it’s likely he played one of his earliest gigs. A moment to catch his breath and wet his whistle in a sugar shack at the end of the road.

Which was a fine idea, except I needed to tell him all about how Southern Accents had changed me on a molecular level. How his songs show that you can love the South but loathe the racism and backward thinking parts of it simultaneously. How it was a complicated, bipolar place to spend your formative years, and if it didn’t kill you, you couldn’t help but come out of there with an artist’s soul. I wanted to make him understand that seeing him on Halloween in 1983 had finally given my Springsteen concert experience a run for its money. And his encore performance of “Rebels” had wrecked me for many concert experiences to come.

I turned and looked at him with such intensity he was forced to make eye contact. Yeah, it was him.

Then, in what I’m certain was my last show of restraint for the next twenty years, I simply tapped the neck of my beer against his, waited for that mischievous, signature Petty smile—part sage, part smart-ass—to reveal itself. Then I nodded and walked away.

In a quiet booth in the back I could almost make out, echoing from somewhere down the lazy river of time, the opening chords of “American Girl” being struck into existence from the heart and hands of a straw-haired boy in a backwoods little bar.

Joe, this certainly is nice writing. Fine word choices and sentence construction. Hat tip. At the same time, it is filled with fact errors that make it tough to take seriously. Possibly you had an encounter with Petty somewhere somehow. But this alleged encounter did not happen as you relate it here.

Comments are closed.