By Eric Yelsa, Ph. D.

The Fall is a wonderful time of year. The majority of cycling events have drawn to a close and with the changes of weather comes an opportunity to reinvest interest in other aspects of life. However, the Fall is also an excellent opportunity to reflect on cycling accomplishments of the past year and develop a comprehensive plan for the upcoming year that allows for development of new goals and a strategy on how to achieve those goals through the upcoming months. The purpose of this article is to discuss the benefits of goal setting and outline how to incorporate a practical goal setting routine into your training so that you can maximize your efforts for the next season.

Have you ever met somebody who wanted to lose weight, make more money, or complete a college degree yet year after year appears to make little progress towards that goal? Chance are they have not made a goal setting plan. Each day we are faced with multiple obstacles that pull us in potentially conflicting directions. Job growth, education, health behaviors, building new social supports, improving financial stability are common areas of life which might benefit from planning ahead. However, these very goals might conflict with each other if attempted at once. Goal setting can assist in identifying those conflicts and develop a framework for prioritizing where focus should be placed and with what extent of effort.

What are goals?

A goal represents an objective, standard or aim of action. It is generally confined to occur within a specific time limit and enhances motivation, confidence, focus, self-awareness, direction and reduces anxiety. It does this by making explicit a series of routines that need to happen in order to move to the next series of routines in a given set of behaviors that ultimately leads to the identified goal. Without goal setting there is no ability to track your progress in an objective manner, no ability to correct for short comings in effort, and no tool to direct energies into an appropriate direction. Goal setting assists to focus the mind to discriminate what is and is not essential in one’s environment in order to achieve a goal, gives you a clear sense of what you must be able to do to meet that goal, and ultimately allows you to identify what you are trying to achieve in life.

The power of different types of goals:

There are two types of basic goals; subjective and objective. A subjective goal is characterized by general statements of intent or desire (“I want to try as hard as I can”). These types of goals have no way to measure their achievement. An objective goal is a specific measurable standard of proficiency on a task that is paired for completion within a given period of time (“I want to complete the May, 2016 Century ride in under 6 hours”). Objective goals can be further broken down into outcome goals, performance goals and process goals. Outcome goals consists of a specific result of an event (i.e., winning an event) and depend to some degree on the ability of other’s performance during the same event. A performance goal focuses on aspects of an event that are independent of the performance of others during that same event. Often times performance goals can be set by comparing one’s previous performance in a similar event (i.e., running a sub 5 minute mile). A process goal consists of behaviors that focus on the actions required during a performance to do well (i.e., committing to climbing to the top of a climb regardless of subjective feeling on a specific day). Each of these types of goals have advantages and disadvantages but when used together can enhance motivational drive.

Most individuals set very general goals. Research regarding goal setting indicates that specific goal setting is not necessarily required for performance enhancement. In one study college students in an 8 week basketball course were placed into two groups one with specific and one with general goals. Results indicated that specific goal development assisted with improvement on low complexity tasks more so than high complexity tasks. However, the wealth of research on goal setting overwhelmingly supports its use as a means for improved performance. Theories on how goal setting influences performance include Locke and Latham’s Mechanistic theory which purports that goal setting assists in directing attention to important aspects of a task, mobilizes effort (such as in a series of goal behaviors), increases immediate effort, prolong persistence and reduces the impact of boredom, and assists in the development of new strategies from experience for goal attainment. Burton’s cognitive theory on motivation suggests that goals are linked to anxiety, motivation and confidence. As we focus on the outcome or winning a performance we may conclude such outcomes as unrealistic. This future orientation lowers confidence which in turn lowers performance efforts. The setting of goals within a time frame assists to alleviate anxiety by developing a series of accomplishable performance levels (mini goals) that can then be viewed as markers of progress towards the larger goal.

Developing personalized and achievable goals:

How do you determine which goals are right for you? The answer should be dependent on review of past performances and a clear vision of what you wish to ultimately obtain. First make a clear assessment of where you are presently. What did you accomplish? How well did you feel and what was your motivation to continue during difficult periods of time in competition? In comparison, how different is your ultimate goal from your current status? This should help serve as a marker for the development of performance markers or mini goals.

When developing goals be sure they are measurable, have a moderate level of difficulty compared to your current status and are realistic. Examples in cycling might include increases in functional threshold power, covering a specific distance or hill climb in a shorter period of time, or maintaining position in a higher ranked category. Be sure to include both short and long term goals, with short term goals representing stairs leading you upwards towards your ultimate goal. These goals should be represented by process, performance and outcome goals, and should apply to both practice and competition situations. State your goals with positive wording and set target dates of when you will achieve such goals. In developing such goals be sure to include strategies on how you will reach each objective. Record your goals in a weekly planner. Place them in a conspicuous place where you will be reminded of them. Provide for feedback opportunities. Provide supports for goals. The following staircase goal sheet worksheet is provided to help you with goal setting.

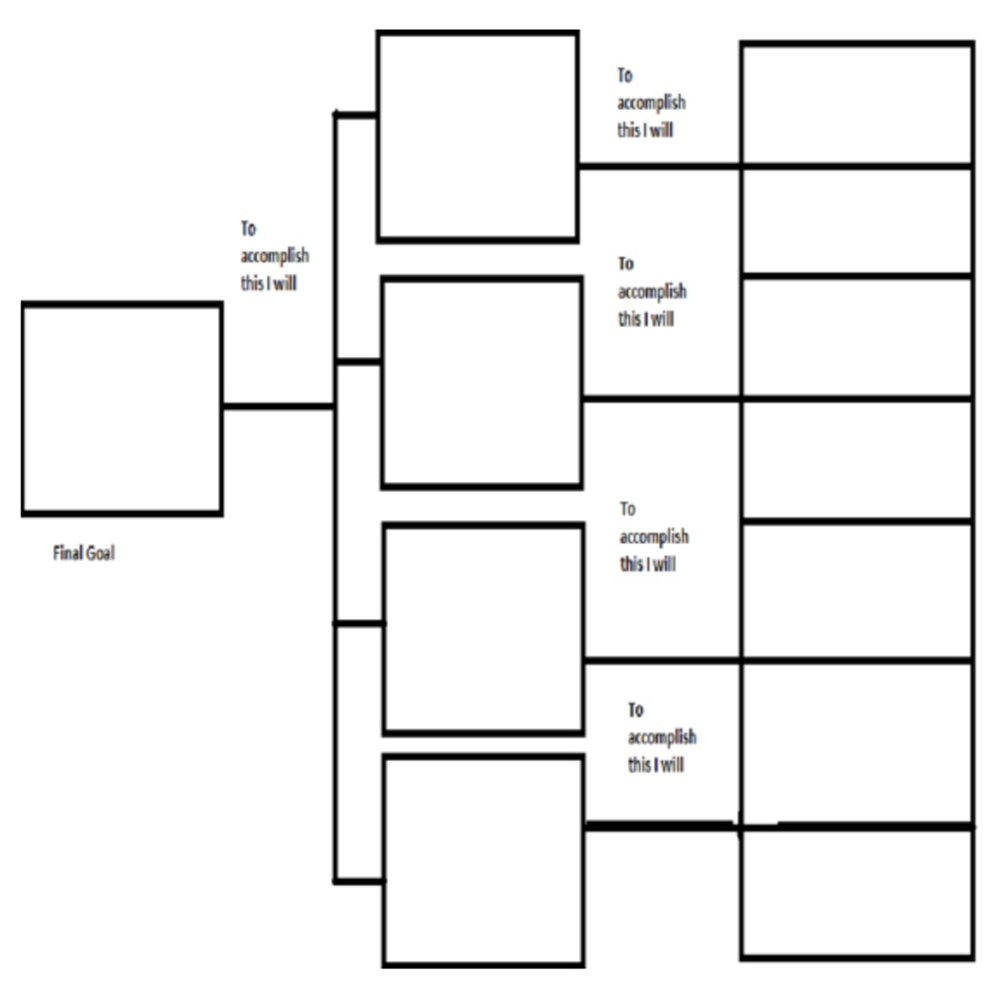

For each performance goal (i.e., one that can be measured and is independent of others ability) use the chart in Figure 1 to create a staircase approach to reach that goal. Place the goal in the left box. Moving to the right, identify the sub-goal to accomplish your major goal. Next, state the performance requirements for each sub-goal. Be positive and specific.

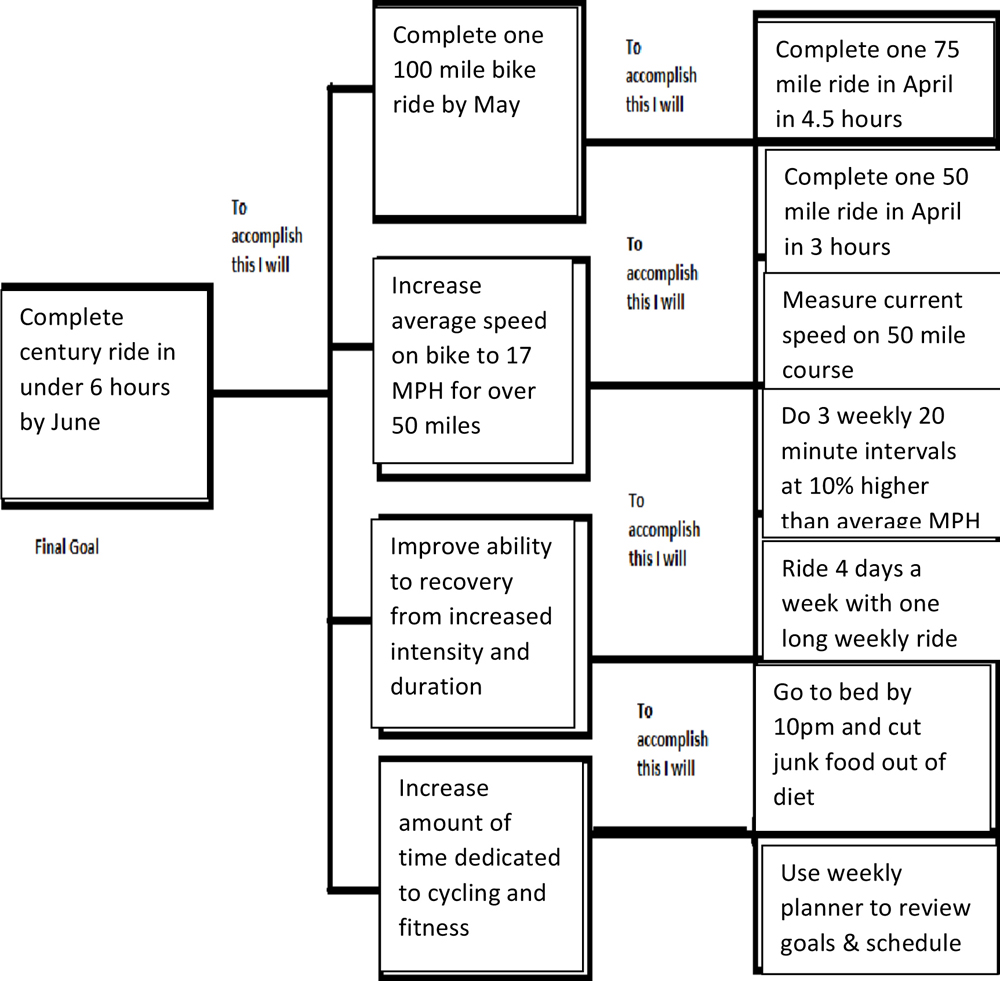

Sample Staircase Goal Sheet:

There are a few suggestions in developing goals. Generally, the body and mind prefer maintaining homeostasis, and dramatic changes in routine can often prompt for a decrease in motivation and increase perceived body exhaustion. Therefore, developing successive goals (i.e., weekly goals) that represent an approximately 10% increase in effort can help to better manage unwanted rebound. Additionally, the types of goals you develop (i.e., outcome, process and performance goals) can have both beneficial and negative impact on motivation. If there is a large discrepancy between your identified goal and skill level then an outcome goal (i.e., “I will win the Tuesday weekly worlds”) may have the adverse effect of decreasing effort. Performance goals (i.e., “I will break my personal best time record”) may also decrease performance if large discrepancy between skill and goal is noted, while process goals (i.e., “I will train daily in some format”) tend to better represent obtainable mini-goals that will then increase motivation towards more difficult goals. In developing your goal plan remember to review it weekly, preferably at the beginning of the week to allow for schedule adjustments. Add in opportunities to re-assess your progress on a monthly basis (i.e., complete a 20 minute time trial to determine increases in speed/watts). Most importantly, make your goals an opportunity to challenge your skills against yourself and have fun. Figure 2 is an example of a completed staircase goal sheet.

Eric Yelsa, Ph.D. is clinical psychologist in practice through the University of Utah Hospital Pain Management Center. He has been a competitive cyclist since 1981. He is a USAC level 3 certified coach, an active member of the Association for Applied Sport Psychology (AASP) and a member of the American Psychological Association Division 47 Exercise and Sport Psychology. He can be reached for consultation at Eric.Yelsa@hsc.utah.edu

References

Burton, D. The Jekyll/Hyde nature of goals: Reconceptualizing goal-setting in sport. In Advances in sport Psychology, T. Horn (Ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 1992, pp. 267-297

Locke, E. A. and G. P. Latham. A Theory of Goal Setting and Task Performance. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1990