“I want to lose weight so other bikers don’t drop me on the hills.”

“I plan to shed a few pounds before the marathon to be faster.”

“Losing weight would really improve my Power to Weight ratio…”

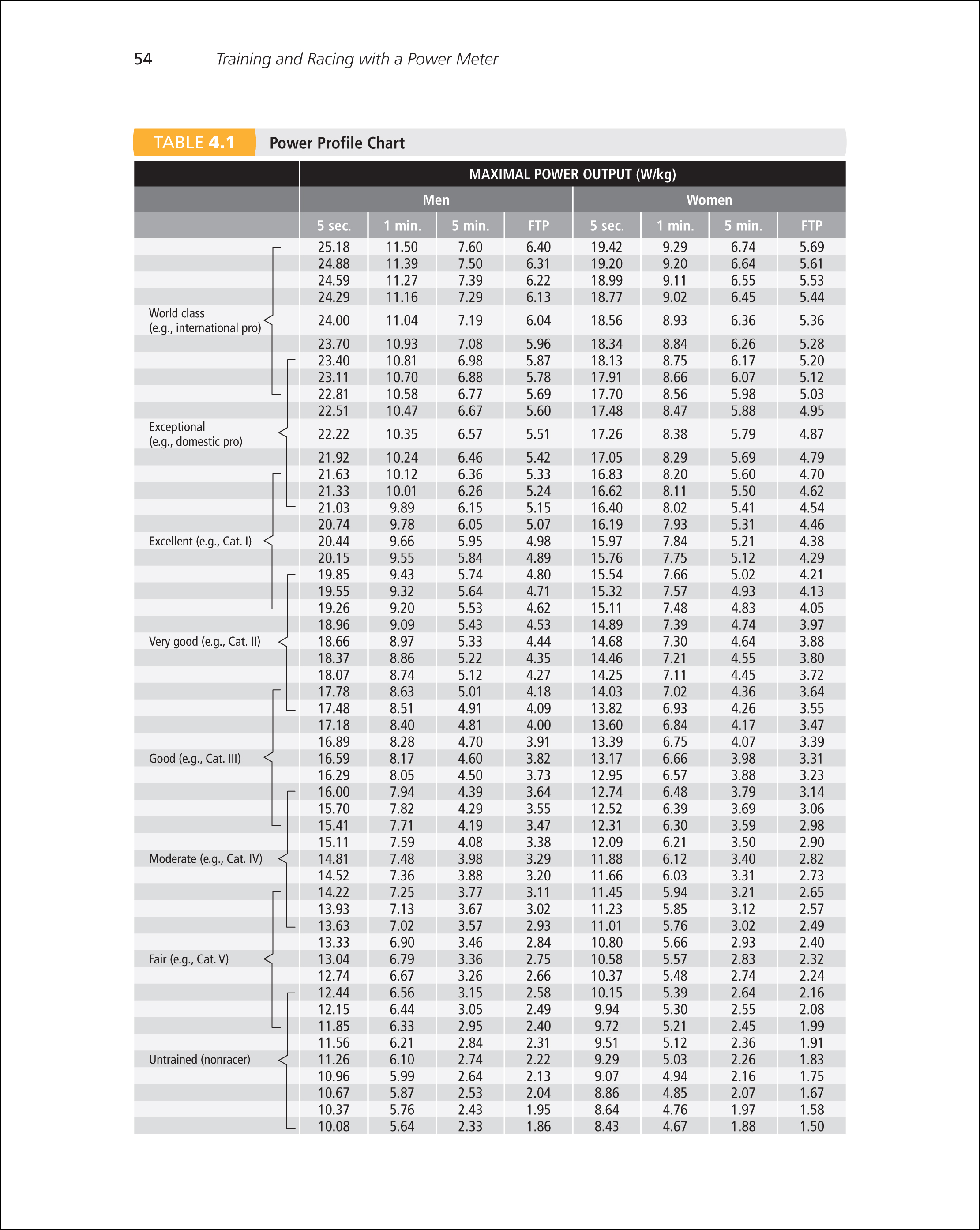

By Nancy Clark MS RD CSSD — Lugging around excess body fat can certainly hinder athletic performance. Just notice how much harder you work when carrying a heavy bag of groceries up a flight of stairs! That said, if you are an already-good athlete and contemplating weight loss to supposedly improve your athletic performance, should you think again? I talk to many athletes who are fixated on having a better Power to Weight Ratio (the power you generate during exercise divided by your body weight).

They overlook the fact that the cost of losing weight (poorly fueled muscles, higher risk for injuries) can limit the benefits of being lighter and supposedly faster, swifter. Here’s some food for thought:

- When pondering the Power to Weight Ratio, most athletes focus on fat loss instead of power gain. Losing fat is hard. (How many people do you know who have been trying to lose the same 5 pounds for the past 10 years…?) Losing fat is even harder if you are already leaner than others in your family. Genetics matters!

- Being lighter and leaner works to a certain extent. Countless athletes have told me they performed their best after having lost weight. Makes sense because their bodies had been training at a heavier weight. The trouble starts when weight-reduced athletes enforce a restrictive diet for months, if not years, to maintain a leaner physique. Injuries start to happen—repeatedly! As one runner who been too thin said, “I was like a race car—until the wheels started falling off. And then the engine dropped out…”

- Among 126 recreational male marathon runners, race times correlated best with training (number and length of workouts, miles per week), not percent body fat—unless body fat was more than ~17%. Runners with 8.5% to 14% body fat had similar marathon run times (1).

- Wrestlers who repeatedly lost the most weight over seven seasons sustained more injuries than those who lost less weight. Cutting weight increased risk for getting injured (2).

- Too many athletes restrict their food (and nutrient) intake to either maintain or attain a desired lightness. Even among top female soccer players, 88% consumed far less than the recommended baseline of 2,300 calories/day. Their average daily carbohydrate intake was only about 200 grams/day—way short of the recommended 350 to 500 grams (2.5 to 3.5 g carb/lb body weight) needed to properly support hard exercise (3).

While these players intellectually knew that “carbs are important for athletes,” they still restricted their carb intake, perceiving carbs as being fattening (4). False! Muscles preferentially burn carbs for fuel. Bread and starchy foods are important for replenishing the muscle glycogen stores that get depleted with hard training and lifting. A high-protein, high-fat chicken Caesar salad doesn’t do the refueling job. More sandwiches please!

- Athletes who take this advice to consume more starchy foods than usual should know they will likely gain a few pounds. It will be water-weight. Each 1-ounce of carb stored as muscle glycogen holds about 3-ounces of water. This weight gain means you are better fueled. Pay attention to how much better your next workout feels!

- Female athletes who restrict their food intake often experience amenorrhea. Under-fed males experience low testosterone and low libido. Both males and females experience low thyroid, low bone mineral density, and have a higher risk for bone injuries. One study reported dieting athletes lost ten-times more training days due to injuries than non-dieters (5).

- Among young girls, body fat gain associated with puberty is often seen as a threat to performance. Some girls go to great extremes to cut back on food and curb the developmental changes that are supposed to happen. Bad idea!!! Restricting food (valuable nutrients) puts them at a three times higher risk of getting stress fractures, as compared to their male peers. About two-thirds of weight-obsessed young ladies will develop disordered eating habits, if not an outright eating disorder.

- Athletes younger than 18 years should not manipulate their body weight (6). Parents, coaches, and teammates alike need learn how to talk comfortably about puberty and the body changes that are supposed to happen throughout middle and high school.

- Super-runner Mary Cain’s story sums it up: “I was the fastest girl in America until I joined Nike” (7) Mary had been shamed about her weight and pressured to get smaller because her breasts and bottom had become too big. She lost her period for three years and broke 5 bones. Unhealthy! Mary Cain’s terrible experience opened the door for many other athletes to become more vocal. The New York Times article “Female college athletes say pressure to cut body fat is toxic” (8) highlighted the need for a culture change that is now happening. Body fat measurements are no longer taken at many colleges.

- Even the military has changed their focus from percent body fat to performance (9). Soldiers need to be strong and powerful. The military now uses Fat-free Mass Index* as a way to track muscle gain, as compared to requiring soldiers to control their body fatness. (*FFMI = fat-free weight/height)

The bottom line: As an athlete, you want to:

- Train to improve performance, not to burn calories. Surround your workouts with food, so you are not exercising on empty, in muscle breakdown mode.

- Consume adequate calories so you are not living in energy deficit during the active part of your day. Being under-fueled leads to lethargy, cold hands, loss of menstrual periods (women) and libido (men), reduced bone health, and less pep—to say nothing of reduced ability to heal and recover from hard workouts.

- Remember that restricting food means restricting important nutrients like protein, iron, zinc, calcium, etc. that reduce your risk for injuries. Drink milk with meals; snack on yogurt. (The current science suggests moderate amounts of dairy fat are unlikely bad for health). Enjoy sandwiches made with peanut butter. (PB-eaters tend to be leaner than folks who avoid this supposedly “fattening” food.)

- Enjoy the success that comes with being well fed, healthy, strong, and powerful. You will always win with good nutrition!

References:

- Tanda, G & B Knechtle. Marathon performance in relation to body fat percentage and training indices in recreational male runners. J Sports Med, 4:141-9, 2013 Open access

- Hammer E. et al, Association of in-competition injury risk and the degree of rapid weight cutting prior to competition in Division I collegiate wrestlers. Br J Sports Med 57(3):160-165, 2023

- Morehen et al. Energy expenditure of female international standard soccer players: A doubly labeled water investigation Med Sci Sports Exer 54(5):769-779, 2022

- Carbohydrate fear, skinfold targets and body image issues: a qualitative analysis of player and stakeholder perceptions of the nutrition culture within elite female soccer McHaffie et al. Sci & Med in Football, 2022

- Heikura et al. Low energy availability is difficult to assess but outcomes have large impact on bone injury rates in elite distance athletes Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 28(4):403-411, 2018 Open access

- Ackerman, K et al. REDS: time for a revolution in sports culture and systems to improve athlete health and performance. Br J Sports Med 54(7):369-370, 2020

- https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/07/opinion/nike-running-mary-cain.html

- https://www.nytimes.com/2022/11/10/sports/college-athletes-body-fat-women.html

- Harty et al. Military body composition standards and physical performance: Historical perspectives and future directions. J Strength Cond Res 36(12): 3551-61, 2022