By Bill Roland –

From July 6–28, 2019, Dr. Massimo “Max” Testa, 63, of Park City, Utah will be “riding” along in his 27th or 28th consecutive Tour de France. Your first question might be, “Omigosh, a rider of that age in the Tour! What team is he on and how can he keep up with those superb athletes?”

Perhaps I should clarify his role in the Tour de France. Dr. Max Testa lives in Park City but every year he serves as the team doctor for a major cycling team that competes in the Tour de France. For the past 12 years he has been with the powerful BMC team. Prior to that he was affiliated with the Motorola and 7-Eleven teams. His responsibilities include everything physical and medical that will keep the riders in top condition to survive riding 2,150 miles in 21 stages over the most beautiful and challenging terrain in France. Dr.Testa is a native of Italy and received his medical degree from the Universita degli Studi di Pavia in 1982. He has been practicing Physical Medicine, Rehabilitation, and Neuromuscular Medicine for more than two decades. Dr. Testa is a physiatrist, a physician who focuses on rehabilitation, restoration of function, and a return to a high quality of life. Dr. Testa’s practice centers on sport and exercise medicine.

At his Cycling Services at the LiVe Well Centers in Park City and Salt Lake City, Dr. Max Testa has worked with professional and recreational cyclists for over 25 years. He not only works with the best professional cyclists in the world but he can show the recreational cyclist how to get faster, ride comfortably, improve power, prevent injuries, train more efficiently, and be properly fitted to their bike. In this article, Max will share with you the inside decisions made by the team managers. He will explain and define what it takes to make the jump from a serious recreational cyclist to one of the top professionals in the world. Basically, you will learn the physical attributes these riders possess and how they are able to withstand such a grueling event. He will provide you with an insight to the strategy of breakaways, the value of domestique riders and what it takes to sprint like Mark Cavendish or fly down the mountain roads in the Alps at more than 60 miles per hour.

A Cycling Team’s Doctor is One Busy Man

A few weeks ago, prior to flying to this year’s Tour de France, Max sat down and explained some intricacies concerning the Tour and exactly what his role will be for the team CCC. “This will be my 27th or 28th Tour de France, I stopped counting a while ago,” he quipped, “I talk to people who watch the Tour de France on television, they focus on the race, but everybody thinks it’s a vacation. Many times, I come back and friends ask, ‘Hey Doc, how was your vacation at the Tour de France?’ It’s not quite a vacation, especially for the staff. You have long days that start very early in the morning and you go all day, sometimes past midnight. You have to transfer every day, from finishing point to the next hotel. On occasion it’s a two or three hour drive. You may have dinner at 9:00-10:00, then you have to go see the riders and change the dressing and take care of any injuries. Sometimes they wake you up in the middle of the night for doping control tests. They may select one or two riders, then you have to go wake the riders, go down to the first floor to the doping control room. Then they might say, we need two more riders, and we go through the whole process all over again. They don’t tell you how many riders are going to be tested or when. Sometimes, you are awake all night assisting the doping control committee. Before you know it, it’s six in the morning, time to wake up the riders, go to breakfast, prepare, transfer the riders two-three hours to the starting point for that day’s stage. There are days, I don’t have time to open the suitcase in my room. I go to bed, wake up, take a shower, boom, out of there.”

At that point, I was exhausted listening to Max’s agenda, but he continued with more interesting detail. “Actually, the doctors have one of the easiest jobs,” he explained. “Especially if there has not been a recent crash. Think about the massage therapists; they have to move all the luggage from one hotel to the next, then give four or five massages at the end of the day. Sometimes starting after dinner. Then they have to prepare two hundred bottles of water for the next day. They work through the night. They make bottles of electrolyte, water, carbohydrate mix, and it depends on the temperature of the next day, the length of the ride and the amount of vertical involved. They modify the water depending on the environmental changes. On average, each rider needs about three gallons of water during each stage. Plus you have to have enough water for each car. Sometimes cars are stuck behind the breakaway and you must have a sufficient number of bottles in the second car.”

Team Managers, What Do They Do?

That was a perfect segue for my next question. I asked Max to explain how many cars are used for each team and what were the responsibilities of those in the cars. “There are three cars per team,” he described. “In the first car, you have two sports directors. One is driving, the other is communicating with the riders. He has the map in front of him, tells the riders if the wind is going to change, you’ll be on a narrow road for five kilometers, then big turn to the right, then you’re going to have a cross wind, and so forth. We have a car ahead on the course and he tells the sports director what the conditions will be in an hour. For example, if there’s a rainstorm ahead and the road will be slippery, he tells the sports director so he can have one or two riders drop back and get rain jackets even though they are miles from the storms. The third car is the service car and I am there with another sports director and the mechanic. If there is a breakaway, we pass the peloton and go behind the breakaway. If there is a bad crash, they drop me out and then they jump in the ambulance with the rider. That’s what happened last year with Richie Porte when I was with the BMC team.”

Dr. Max Testa was with BMC for 12 years. Before that he was the team doctor for Motorola, and prior to that he was with the 7-Eleven team. The CCC is comprised of about 30% of last year’s BMC team. Needless to say, over the last 28 years he has provided quite a bit of medical attention to many riders in the Tour de France. The CCC team existed on the continental level and BMC had the UCI World Tour license and joined forces with them this season. CCC is a Polish phrase that means “The price makes miracles.” It was a logo used by a company that manufactured leather products, primarily purses and shoes. The team is co-owned by American Jim Ochowicz, who founded the 7-Eleven Cycling Team and is presently the team manager. Although the first stage of this year’s Tour de France is on Saturday, July 6, Max will fly over on Tuesday July 2. He must be there three-four days ahead for the anti-doping tests for the team. Normally the doctor is there witnessing the doping control of his team. There are reports and paper work to get in order.

Tour Riders versus You: What’s the Difference?

Max was asked what the main difference was between recreational riders and those professionals competing in the Tour de France. “Power is the main difference between those who ride the Tour and everyday riders,” he explained, “or even serious competitive cyclists who are not on the same level. We look at strength and talent as the number of watts you can push for a given amount of time, and the ratio between weight and power. For example, you take the amount of watts you push for a climb that takes 30-40 minutes, then you divide by body weight and you have watts per kilo. That’s what makes your speed going uphill.

“So you take the winners of the Tour de France, and they win mostly on the climbs. In comparison, take a Cat 1 cyclist, who trains 15-20 hours a week and imagine he is on a major climb after four or five hours on the bike. He can average 4.5 to 5.5 watts per kilo while a fit recreational rider will average 2 to 3 watts per kilo. So if a Cat 1 rider, the fittest guy locally, averages 4.5 to 5.5 watts per kilo, the Tour de France top riders are between 6.3 and 6.8. So they can go up about 10 per cent faster than a good local regional level cyclist. Pretty much a Tour de France rider climbs double the speed of a good, well fit recreational serious rider. They can go up a steep grade at 15-18 miles an hour.”

When asked, what is the ratio of watts to kilos, he responded, “Say a rider is pushing 420-440 watts for 45 minutes, then you divide by body weight, which is about 65 kilos, and that number determines how fast they can climb. The higher the number, the faster you go up. So you take a good cyclist that pushes 250-300 watts, say you divide by 75 kilos, or 165 pounds, the ratio is much lower. It’s like a big engine mounted on a light frame.” In simpler terms, watts measure how hard you work. For example, six-time Tour de France stage winner Andre Greipel, can generate a charge of 1,900 watts of power in a single sprint. Mark Cavendish says he sprints at 1,500 watts. Most pro cyclists produce close to 300 watts on average during a four-hour tour stage.

I was anxious to hear about how these Tour de France riders became so strong, fit, and skilled. “The condition of these riders is genetically determined,” Max explained. “They are born with this gift. On top of that, they have training and a career and have been racing since they were 8-9 years-old. So they have the skills, they know how to envision the race and everything that comes with learning the techniques. They understand the race; one day you have to chase and attack and the next day you don’t. For example the gift that a 7-footer has on the basketball court is visible. But the gift these guys have, that they have been born with, it’s in the quality of their lungs, the quality of their heart, the quality of their muscle, their ability to generate power in the mitochondria, an organelle in the cytoplasm of cells that functions in energy production. In a good way, they are a freak of nature. Some of these people deliver 70-80 milliliter of oxygen every minute per kilo of body weight.The normal person has 25-40. These young people can process oxygen at double the normal speed. Training can contribute 10-15 per cent of VO2 Max (milliliters of oxygen per kilo of body weight) the amount of oxygen they can deliver to the muscles. It’s just that they have a different engine. It’s like having a furnace that runs at double the normal speed. When I was in Milan, we tested 800 juniors every year when they were 12. And when they were 14-15 you could see the ones that were 70 plus VO2. You could see who would become good professionals. In the ten years we brought a lot of juniors to become pro because we have monitored them since age 12. It was a pipeline.”

Tips on Staying Healthy

As far as recreational riders are concerned, I asked Max if he had some advice so riders could avoid time off the bike during the season and stay healthy. “If the pain is a series of aches,” he surmised, “moderate your training so that you have enough recovery days especially if you are older than 40 or 50. Because as you grow older, recovery takes longer. You can still train hard but you might need two or three light days before you train hard again. Stretching can help but one of the first pieces of advice is to make sure your position on the bike is correct. Because if you are sitting in the wrong position, too low or too far forward, you many have more knee or quad pain. If you are sitting too far back, you may have more hamstring or glute pain. It’s important to start with a good bike fitting. If the position is correct, work on your training organization so you have days that you train hard but days when you can recover. Another thing is to do everything you can do to optimize your recovery. Stretching is one, sometimes a cold bath after a long ride could help. Also, make sure you have good nutrition for recovery, so after you are done you have your shake with protein and carbohydrates, in order to speed up recovery. These are good recommendations but everything starts with a good bike fitting and a good training program.

“Then there are complicated cases where you have the person that does everything right but he or she has a bad knee that happened playing football, tennis, or an assortment of sports injuries and they have chronic knee pain. Sometimes, we do what we call ‘medical bike fitting.’ We do anywhere between 300-500 a year right here. Some people come in with their bike, not because they have a wrong position in terms of fitting but because they have knee or neck pain. So we adjust the position to reduce the load on the knee or the achilles or the neck or whatever. So we put together the medical condition of the patient, their flexibility, with the position. That may prevent them from being a super fast rider but allow them to ride without a lot of pain.”

Intervals

Regarding training, I looked forward to hear Max’s opinion on the role intervals play for professional cyclists and recreational riders. “I think intervals are more important for recreational riders than pros,” he explained, “because the pros race or train 20-25 hours a week. They ride over all kinds of terrain, so naturally intervals are included. The intervals tend to give the rider more in return for the time invested in training than steady training. Steady training is good for recovery days or training for a long event. Intervals are good but as you get older, you tend to lose the top end. You can still go long but people my age prefer riding long and steady because it feels natural. It’s easier than riding hard. But I do recommend that seniors in good condition, should introduce intervals in their training at least one or twice a week.”

Peter Sagan, Paul Sherwen, and Bob Roll

Max mentioned that Peter Sagan had been up here training for two weeks in Park City. Pete just left in early June, 3-4 days before the Tour of Switzerland, and by the time we did this interview he had already won a stage. “He comes here a couple times a year,” Max recalled, “Peter rides all around the Park City area, six hours a day and that includes many canyons here on the Wasatch Front. He spends a lot of time on a mountain bike, that’s his background and a major part of his training.”

While talking about his time with the Motorola Team from 1991-1996, Max mentioned that for five seasons he was a roommate with Paul Sherwen, who at that time was the PR-Media Representative for Motorola. As many readers know, Paul Sherwin died suddenly at age 62 of a heart attack in early December at his home in South Africa. Following his time with Motorola, Sherwen became affiliated with Phil Liggett and the duo became professional cycling’s best television broadcasters by a long shot. I asked Max about his friendship with Paul Sherwin. “I got to know Paul very well and like everyone I appreciated his friendship,” Max recalled, “but he was much more than a nice guy. He was super smart, a very good rider in the 80’s but extremely passionate about the sport. He knew so much about the culture of cycling, riders from the past and the present and his memory was unbelievable. He could have been a great Sport Director or Coach because he really understood the sport.”

During the same time in the 90’s, Bob Roll was a rider for Motorola and Max was the Doctor for the 7-Eleven team. Once a year Bob comes to Park City to get his physical for insurance purposes. Max recalled that a few years ago after Bob turned 50, Max asked him when he had his last physical. Bob’s reply was, “When was the last time we were together during the Tour de France?” That was some 20 years ago but now he gets his physical annually. Max reassured me that the humor Bob Roll shares on television is not designed solely for the camera. “That’s Bob,” Max reiterated, “he’s very genuine, has a sense of humor, sometimes hard to understand or pick up but he’s a fun guy to be around. We ride together every November; a weekend with a group from Colorado in the Moab area. He’s still a very strong rider, he can keep together with the young guys.”

The Peloton’s “Domestique Riders” are Invaluable

Despite an avid viewer of pro tour racing, this writer never thoroughly understood the role “domestique” riders provide to each team and how they are selected. The dictionary defines a domestique as a member of a bicycle-racing team who assists the leader by setting a pace, preventing breakaways by other teams, or supplying food and water to team members. It took Max no more than a split second to define the importance of the domestique rider. “Cycling is a team sport,” he described, “even though there is a perception there is a winner, but most of the time, the winner could not reach that plateau without the support of the other riders. What happens in the pro peloton, is that by a certain phase of your pro career, you realize that you are good enough to be a leader, so that you can deliver on the day of the big races. You can be an overall prospect for stage races, or a one day specialist. If you’re not quite there, maybe shy by only two-three percent, you realize you can be a domestique. They play an amazing role. Some keep their teams leaders out of the wind, they go back to the car and get bottles (sometimes more than eight or ten) of water or electrolyte drinks, jackets if a rainstorm is coming, and of course they make sure their teammates have food and fluid throughout the race. One time we had a rider who was a domestique but because other teammates were injured, he rode out front and finished second in the Tour of Switzerland and tenth in the Tour de France. If you are a team manager and build a team, you identify your team leaders but you also find those strong riders who can play the role of being a helpful and successful domestique. Each team looks for the best domestique rider and it’s no surprise, they are in high demand. For example, you take last year’s SKY team. Of the eight riders on the tour team, you have six that could be leaders on any other team. Those six riders, cost more than the budget of most of the other teams. The budgets are really different between the intermediate level teams compared to those at the top.”

How Does the Peloton Catch up with the Breakaway Riders?

I posed that question to Max and it took him less time to reply than it takes many of us to change gears. “Maybe they don’t have a precise mathematical formula,” he explained, “but by rule of thumb, you know how much you can gain every 10 kilometers if you have two riders pulling, or three, or even four riders. Normally, the strategy is to let the breakaway go, knowing there may be more than one team motivated to chase. Maybe the riders in the breakaway can bother more than one team for overall, for intermediate sprints or whatever the situation. If there are three or four teams in the peloton that want to bring the breakaway riders back, most of these teams have sprinters and they want the race to finish with a sprint. Another situation is that a rider in the breakaway might be in position to pass the overall leader. A rule of thumb, as I said, is that the peloton can gain one minute every ten kilometers (that’s 6.2 miles). Despite the number of riders in the breakaway, say there are 12, not every rider is necessarily working, doing his part, taking pulls. Sometimes only five riders are working because a rider might know that if this breakaway works, my teammate, who is currently in sixth position, may fall back to eighth. So they stay passive in the breakaway. If they pull, they do the minimum so not to be kicked out of the breakaway.”

If the breakaway fails, let’s use the term dissolves, with just a few kilometers remaining, sometimes the body language of a rider who has been in this breakaway, speaks volumes. Needless to say, Max had the perfect response. “In the Tour de France, you are happy to be in the breakaway for 100 miles, even if they catch you,” Max replied. “First of all, the rider will be on television for two-three hours, the sponsor is happy because the camera keeps showing the jersey, the rider’s name has been mentioned over and over, so it’s nice to have your name mentioned many times on the international stage.”

The Tour Riders Descend So Fast? Yikes!

After watching the Tour de France riders climb a most challenging mountain in the Alps or the Pyrenees that lasted quite some time, our first reaction is to breath a sigh of relief even though most of us have no idea how difficult that ascent really was nor do we feel the pain that every rider is going through at that very moment. But we have some idea what lies ahead because the commentators have briefed us that the descent may be in the 5-7 mile category and these riders will be approaching 60 mph or more. How do they do it?

“First of all,” Max remarked with a smile, “this is second nature to many of these riders. They have been descending mountains like this since they were 8-10 years old. Sometimes, you see a big difference in skill going downhill. Some are not very good and make square turns rather that making the turns as straight as they can. This comes with practice. Also, using the brakes properly is very important. A tip is not to hold too long on the brakes because you can heat up the wheels, especially the carbon fiber wheels that heat up quickly. Let the bike go; you can sit up or even stand to allow your body mass to slow you down. Make sure you use the brakes progressively and not lock things up. And when you are getting out of a turn, let the brakes cool down a little so you’ll be ready for the next turn. For the recreational cyclist, I recommend not to increase your speed even more when you know you have a steep pitch right ahead and you’re going to need your brakes again. Disc brakes are a good option if you are coming down a lot of steep canyons. These pros on the tour try to limit the overuse of their brakes and they go with the flow of the riders in front of them. My recommendation is to be aware of your skill level and not try to go too fast for your ability and avoid over using the brakes. Be cautious, practice in training, maybe on the low grade hills first, that are not so steep. Learn to shift your weight a little more on the inside like the motorcycle riders do.”

As the interview came to a close, we shook hands, thanked each other for the time, but I felt it necessary to share one message with Dr. Max Testa. “Max, have a great experience during this year’s Tour de France, but I hope you never have to get out of the car and help a rider who had an accident.” His response was short and right to the point. “Bill, that’s our goal, every year!”

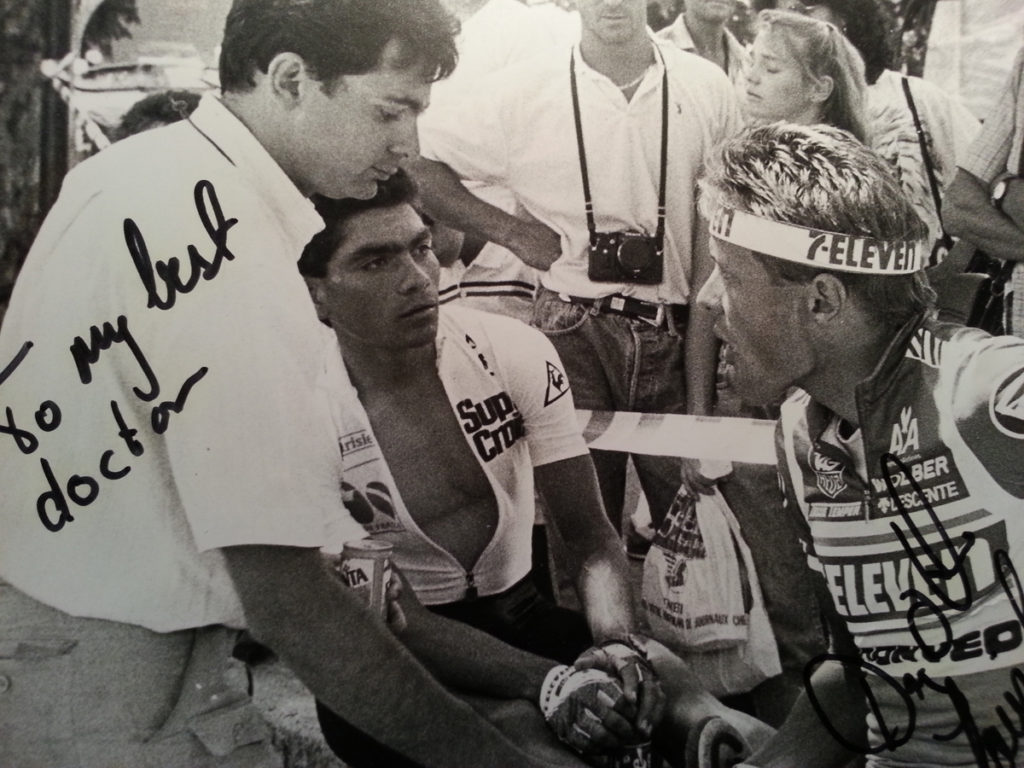

The picture with Raul and Dag-Otto is from 1987. Andy Hampsten wore the white jersey in the 1986 Tour de France.

The photo with Max and Bob Roll is from the 1986 Tour.

Great article Dave!

Great article.

Thank you.

Comments are closed.