during the summer.

Logan Canyon, served by U.S Highway 89, is the feature attraction in this ride up and down one of Utah’s eight national scenic byways. As described on the U.S. Department of Transportation’s byways website, “This byway provides spectacular scenery and access to great recreational areas. It begins at the mouth of the canyon on the east edge of Logan. Deeply cut, nearly vertical limestone walls and rock formations laden with fossils greet travelers entering the canyon. The Logan River, popular for trout fishing, parallels the route, offering yet another reason to stop and spend some time. As autumn approaches, lush greens of this high mountain passage tipped with brilliant gold, red and yellow can be seen throughout the route. The route explores the spectacular Wasatch-Cache National Forest.” Mountain wildlife can occasionally be viewed as well, including deer, moose and, on very rare occasion, bear (!).

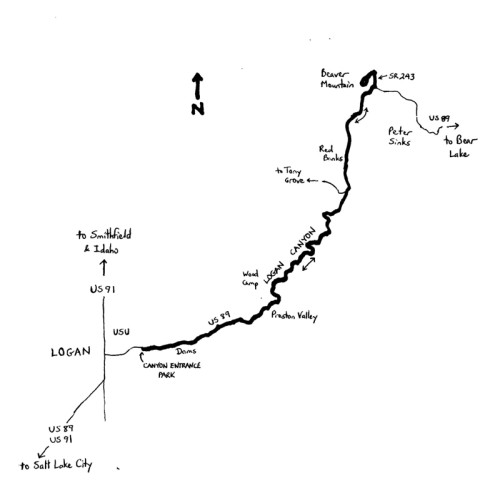

The Logan Canyon Challenge is, as suggested, a challenging 55.0-mile ride out and back through Logan Canyon, including a climb to the turnaround point at Beaver Mountain. The low elevation is on U.S. 89 at the mouth of Logan Canyon (4,706 feet), while the turnaround at Beaver Mountain, at the end of State Route 243, is at 7,247 feet (for an elevation differential of 2,541 feet). The climbing is primarily gradual, with the steepest segment coming at Beaver Mountain. As indicated in the byway description, start the ride on the eastern edge of Logan, at Cache Valley’s “east-side gateway.” Canyon Entrance Park is conveniently located on Canyon Road, just south of U.S. 89, near the mouth of Logan Canyon. Turn right upon leaving the park, and then turn right again onto U.S. 89. The highway is the main route between Cache Valley and Bear Lake, and is an alternative to the Interstate freeway system for travels to Idaho. Traffic volumes ranged from just over 6,000 vehicles per day close to the mouth of the canyon to 3,000 vehicles per day near the Beaver Mountain turnoff in 2012.

The ride begins to climb gently as you enter Logan Canyon. The highway has two lanes, with a variable shoulder width, although reconstruction of various segments (particularly bridges) was occurring as of this writing. The Logan River flows to the right. Enter Wasatch-Cache National Forest just 0.6 miles up the canyon. The canyon walls are steep and dramatic; layers, representing different geological eras, are visible in places. There are numerous trailheads and pullouts along the way; always watch for entering and exiting motor vehicles. Campgrounds are plentiful, as well, including Bridger at mile 3, Preston Valley at mile 8, and others. An excellent brochure – “Guide to the Logan Canyon National Scenic Byway” (Cache Valley and Bear Lake Visitors Bureaus) – lists 31 sites and stops to make along the canyon. Stopping every mile may not be practical, and there are too many to describe here, but you are encouraged to slow down, or even take a diversion, to absorb a few of the canyon’s wonders.

Access to the Wood Campground – Boy Scouts Camp is on the left at mile 10.2. The elevation here is 5,357 feet, meaning that you have been climbing at a gentle 1 to 1.5% grade. There are a number of river crossings – and bridges (see above) – such that the Logan River shifts between your left and your right. Logan Cave is on the left at mile 11.9; the mouth of the cave is up on the cliffs. The cave extends some 4,000 feet into the mountains. The cave is not accessible, as it serves as the protected home of Townsend’s big-eared bat. The canyon “opens,” and the highway grade increases, around mile 13.3, enabling vistas beyond the canyon walls. Some of the highest peaks of the Bear River Range loom in the distance at mile 17.4; Swan Peak juts upward to 9,082 feet. The turnoff to Tony Grove is at mile 19.6 – a highly-recommended diversion, in particular for the wildflowers that bloom around the grove’s glacial lake. (Note that it is a 7-mile trip to Tony Grove).

At mile 22.2, the highway grade kicks up again. Enter an alpine environment at mile 24.6, notable by the evergreen and pine trees. At mile 25.7, turn left onto State Route 243, to access Beaver Mountain. (Note that U.S. 89 continues to climb from here to a summit at 7,800 feet. From there, it is a dramatic descent to Garden City and Bear Lake). Note that, a few miles east of here, but not along the highway, is Peter Sinks, known for being the coldest spot in Utah, and second-coldest in the contiguous U.S. This is a natural sinkhole that experiences temperature inversions. A record low of -69.3oF was measured there in 1985. Below freezing temperatures are known to occur even during the summer, and no trees grow in the sinkhole. The mile and a-half jaunt to the “Ski the Beav” resort serves as the turnaround segment. Beaver Mountain is the oldest, family-run ski resort in the U.S. Enter the resort’s parking area at mile 27.2, and then follow the loop around and out. Note that the resort is active during the summer, with camping, water sports, and trail-related activities. Upon exiting the resort, descend State Route 243 to U.S. 89. Turn right here to begin the long descent of Logan Canyon. Given the gradual climb outbound, it is not a freewheeling descent; so, expect to do some pedaling. After leaving the canyon, return to Canyon Entrance Park to conclude the ride.

For more rides, see Road Biking Utah (Falcon Guides), written by avid cyclist Wayne Cottrell. Road Biking Utah features descriptions of 40 road bike rides in Utah. The ride lengths range from 14 to 106 miles, and the book’s coverage is statewide: from Wendover to Vernal, and from Bear Lake to St. George to Bluff. Each ride description features information about the suggested start-finish location, length, mileposts, terrain, traffic conditions and, most importantly, sights. The text is rich in detail about each route, including history, folklore, flora, fauna and, of course, scenery.

For more rides, see Road Biking Utah (Falcon Guides), written by avid cyclist Wayne Cottrell. Road Biking Utah features descriptions of 40 road bike rides in Utah. The ride lengths range from 14 to 106 miles, and the book’s coverage is statewide: from Wendover to Vernal, and from Bear Lake to St. George to Bluff. Each ride description features information about the suggested start-finish location, length, mileposts, terrain, traffic conditions and, most importantly, sights. The text is rich in detail about each route, including history, folklore, flora, fauna and, of course, scenery.

Wayne Cottrell is a former Utah resident who conducted extensive research while living here – and even after moving – to develop the content for the book.