By Mel Bashore —

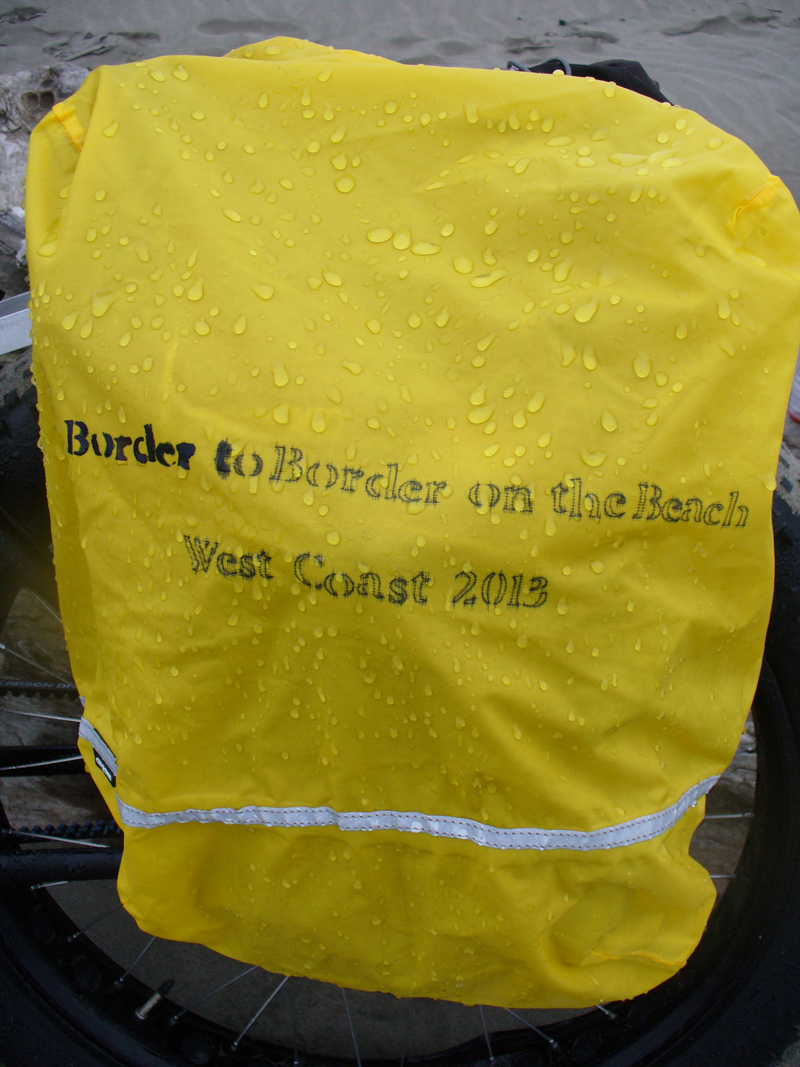

Only one week after my 67th birthday and just days after retiring from a fulfilling career, I set out from Salt Lake City on a solo bike tour that, as far as I could tell, had never been undertaken by anyone ever before. In this day of worldwide adventure cycling, concocting never-before undertaken ventures is almost inconceivable, yet I found no record of anyone ever attempting what I hoped to accomplish. I set off to ride, as far as feasibly practical, on the U.S. west coast from our border with Canada south to our border with Mexico. Many bike riders have ridden that distance on the coastal highways, but I wanted to ride from border to border on the beach, that is, right on the sand. As far as I could tell, no one had ever tried it.

The idea to ride on the beach really started two years ago on a bike ride I took up the coast of Oregon, through the Columbia River Gorge, then home through Idaho to Utah (see Cycling Utah, Fall-Winter 2011 issue). On the Oregon coast segment of that ride, half the time I could not even see the ocean because U. S. Highway 101 was too far inland. That was disappointing.

A few months after returning home, I was working on a book manuscript (still in progress) about an amazing bike rider who rode around the perimeter of the United States before 1900. He rode his bike (then called a safety) on the beach in California between Ventura and Santa Barbara. A light bulb came on for me. If I could ride on the beach, I would see much more of the ocean than if I were to ride the coastal highway. How would it be to ride the entire length of the U. S. west coast? How would it be to sleep on the sand each night, lulled to sleep by the sound of the waves?

This grand idea sparked a litany of questions. Had anyone ever ridden on the beach the entire length of the U. S. west coast? What kind of bike would it take to do it? How long would it take to undertake and complete? How many miles of actual beach riding were possible? If the ride had never been done before, what resources could I use to plan the route?

Although I was unable to find a record of anyone ever attempting such a ride before, I didn’t discount that possibly someone had tried it. I had certainly seen beach cruisers riding on the sand, but had never seen anyone seriously touring any great distances on the beach.

I began casting about, talking with others, to try to figure out what bike might hold up on a really long beach ride. Having ridden a Surly on long tours for several years, I was partial to their big-tired bikes like the Pugsley and Moonlander. Riding back from Yellowstone in 2012, I ran into two fellows heading north just south of the South Entrance of Yellowstone. One was riding a Pugsley and the other a Moonlander. I told them about the West Coast ride that I was contemplating. They invited me to give their bikes a try. I liked the feel of the Pugsley and began thinking that might be the bike for me.

But before I ventured down that path, an interesting turn of events took me in an altogether different direction. One of my sons is in the shipping business. Fortuitously for me, he visited a bike business headquartered in Ogden (until recently – now they are back in Anchorage, AK). FatBikes.com, makes a bike that is tailor-made for sand or snow. Not only does it have the fat tires (like the Pugsley), but it has a carbon fiber belt drive and no external metal cluster of gears; its drive train is encased in the rear hub. Its design gave promise that its drive train wouldn’t get damaged by gritty beach sand. I bought FatBike’s 9:Zero:7 Tusken.

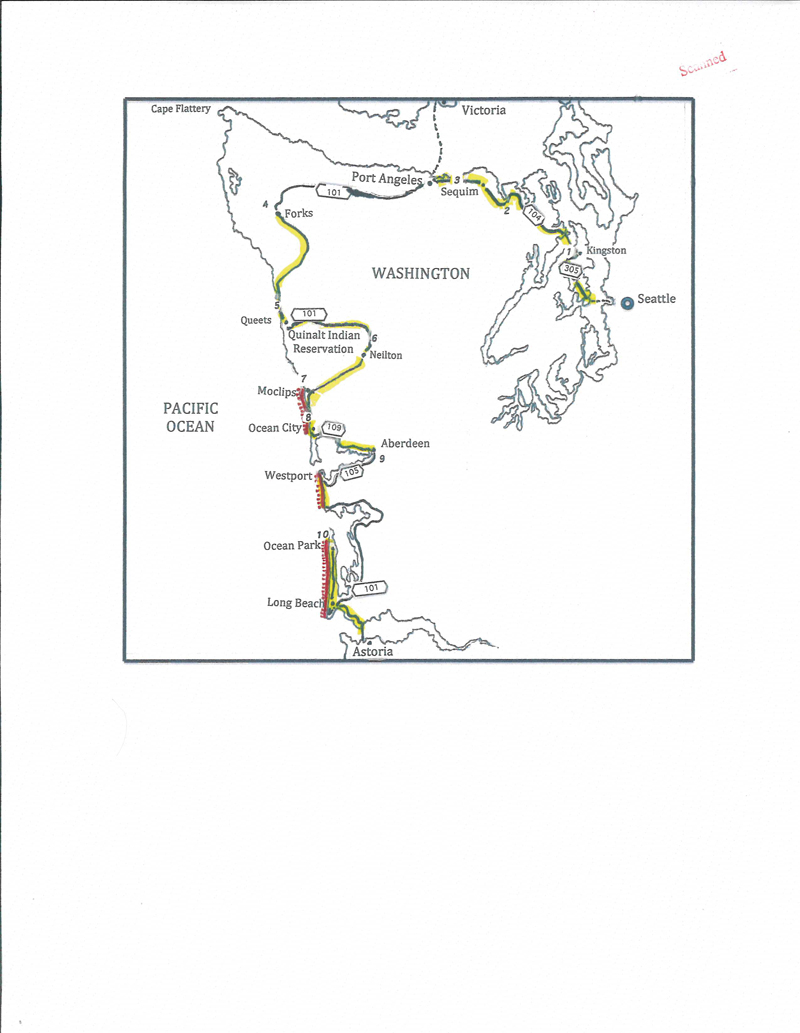

I then spent about ten months planning the route of my ride, using Google Earth and the Internet to research it. I left Salt Lake with my maps and research notes in early July 2013, my bike crated in a bike box provided by Amtrak. I had used Amtrak for transport on a ride previously and, although the departure hours out of Salt Lake weren’t real great, the ease in transporting my bike had made up for it.

The Ride

The train arrived in Seattle near dusk. Fortunately the hostel where I had booked to stay was only a few blocks east of the train station. After retrieving my boxed bike from the baggage department, I joined a few other cyclists in the cavernous lobby who were uncrating their bikes. I began cutting the duct tape and slid out the bike. I was shocked to discover that my rear rim had been severely dented by the baggage handlers. Like a dummy, I had failed to insure it. As I thought about it, I realized that it may have been mostly my fault. In order to make this oversized bike fit in the box crate without bulging unseemly on the ends, I had deflated the tires too much beyond a safe cushion. The rear of the heavy box may have come down hard on the upright edge of a baggage cart. End result: damaged rim.

But with it quickly turning dark, I needed to reassemble the bike, get safely to the hostel, and try to deal with the rim problem in the morning. After pumping up the tires and getting my gear on the bike, I sallied forth from the station to find the hostel. I could feel a slight thumping from my dented rim, but was comforted to see that it seemed to be holding air. After reaching the hostel located on the edge of Seattle’s Chinatown, I stowed my bike in their secure basement and tried to put my worries behind me and fall asleep.

After a fitful night I awoke and joined dozens of other excited young people in a community kitchen in the hostel. A helpful concierge gave me contact information for some good nearby bike shops. I needed some advice on my situation. A knowledgeable repairman at a Seattle bike shop ruled out pounding the rim back into shape because I would risk cracking the aluminum rim.

That left me two other options: try riding it or send for another rim. I really didn’t want to wait around downtown Seattle for a replacement rim to be shipped. I thought if I could do the ride I had planned through Washington on the dented rim, I could have a new rim shipped to Astoria, Oregon, where my brother lived. I would rather spend a few days with my brother than in crowded downtown Seattle. The bike repairman concurred with that plan and suggested riding a few miles to see if the tire would hold up. If it seemed to be stable and I rode carefully, he thought the odds were good that I could make it to Oregon.

With that plan and my brother’s assurance that he would come to my rescue if needed, I set out on the short ride down to the pier to take the ferry across Puget Sound to Bainbridge Island. The hostel concierge had told me about two good bike shops on the island if I needed to seek repair help before getting beyond the metropolitan area.

Although I set out with a mind full of questions and doubts, the excitement of the ferry ride dulled those negative thoughts somewhat. I disembarked from the ferry onto the island hoping that this dented rim would only be a minor snag in my long-awaited adventure. New sights greeted me and brightened my outlook as I made my way inland and toward the coast.

On past bike rides, I have purposely done little research or mapping in advance, preferring to experience serendipity and adventure more fully by taking that approach. But the complication and difficulty inherent in this long ride necessitated a different course. Hemmed in by tall trees much of the time, I had to be watchful and careful in picking my way among the various roads, lest I take a wrong turn and go miles out of my way.

On the very first day of riding, I wasn’t careful and ended up riding ten miles out of my way. At Kingston, I stopped to get something to eat at a grocery store. As would happen at most places, curious people asked me about my unique bike and what I was doing. I mention this because one man who shared a bond of biking, expressed great concern for me and my dented rim. Mo Y. gave me his business card and urged me to give him a phone call if I needed transport help while in the state of Washington. The kindness of people like Mo, are not soon forgotten. He also told me how to find places to camp in Washington’s deep woods—a pointer that I employed several times including on that first night.

For whatever reason, I became turned around or wasn’t careful in getting back on the right road at Kingston. After that careless little ten-mile detour, I returned to Kingston and got back on track. That evening I picked a promising steel-gated forest access road for my first night bedding down in Washington’s woods.

On my second day and thereafter, I checked my map and notes twice at any fork of the road. I had learned my lesson. Early in the morning, I biked through the historic town of Port Gamble with its manicured lawns and clapboard houses. A few miles later I crossed the long bridge across the Hood Canal and then dove back into the woods on State Highway 104. I was aiming to camp at a hiker-biker camp at Sequim Bay State Park that night. This would be a step above my usual “sleep in a ditch” accommodations. Unfortunately just west of the small hamlet of Blyn, I got a flat tire. Rear tire of course. This slowed me down and I ended up “sleeping in a ditch” on the Olympic Discovery Bike Trail. I had to bed down a few miles shy of my goal when I ran out of daylight.

The next morning, the bike trail took me through Sequim Bay State Park past the hiker-biker camp. Drats! I had missed a good camp. The Discovery Trail presently runs from Port Townsend to Port Angeles, barring a few gaps here and there. Even though unfinished, it is a gem. There are plans afoot and funding in place to make this a world-class trail stretching for 125 miles to the coast! (more on this later) The ride on the bike trail was such a delight and far from traffic that I lingered at a slow pace. If I had stepped things up, I could have easily made Port Angeles, but I wanted to time my arrival there for the morning in order to take the ferry to Victoria, Canada.

As I pedaled through a rural area east of Port Angeles, I spotted a hand-painted sign next to the trail—Free Camping. Really? Yes, really. That night I slept under a roof in a rustic shelter on a comfy foam mat—courtesy of kind-hearted Lonnie, proprietor of what he calls The Rest Stop on his land. Another generous soul with a heart of gold. I know that long after I have forgotten about the places I’ve ridden or flat tires and dented rims, I will still remember the good souls I’ve met on my bike adventures.

Good fortune continued to smile on me as I pulled into Port Angeles. I enjoyed a hearty breakfast at the Corner House Café. For a stretch of several miles before reaching town, the bike trail paralleled the south shore of the Strait of Juan de Fuca—the water lapping just a few feet to the side with vistas across to Canada. Primo biking! After breakfast I waited with others to cross the Strait to Victoria, Canada. I needed to do this if my effort to travel from border to border on the beach was to be authentic. I boarded the ferry, locked my bike on the foredeck, and found a seat inside.

During the ninety-minute, 22-mile crossing, I thought about the journey ahead. My pace so far had been tortuously slow. It had taken me three days to cover ninety miles. At that rate, I might not get home until Christmas! I was used to averaging about seventy miles per day on my other Surly touring bike. It wasn’t just the dented rim, but the friction of really big tires on the paved roads and trails that was slowing my pace. I needed to get to the beach where this bike could really perform (or out-perform) anything else on two wheels. But the coast seemed far, far away.

At that moment I decided to change course when I got back to Port Angeles and take a more direct route to the coast. Instead of going out to Cape Flattery, the northwestern-most point of the contiguous United States, I decided to take U. S. Highway 101 to the coast. I would forego not riding a miniscule couple of miles of beach riding (if that) on the coast just south of Cape Flattery for the more direct route to coastal beaches. It would save me more than a hundred miles of highway riding. I would miss seeing a dramatic rocky shoreline, but my slow pace dictated making some concessions.

My mind made up about this course correction, I was free to enjoy the rest of the crossing into the busy port of Victoria. I was entertained by passengers sighting whales and people taking pictures of my bike. With a new route plan in mind, I decided to simply disembark briefly, go through Customs, and re-board the ferry for its return journey to Port Angeles. I had to make tracks.

After a brief touchdown on Canadian soil with my bike, I re-boarded. While stowing my bike on the foredeck, a curious man began asking me about my bike. Erik R. and his wife, Carrie, were just returning from a week-long bike tour around Vancouver on a tandem. When I told him that I had decided to change my route and go south on Highway 101, he became quite concerned.

He feared for my safety on the narrow-shouldered twelve-mile stretch of highway where it bordered Lake Crescent in the Olympic National Park. It was the scene of numerous fatal bike-car accidents. He was concerned that on a Sunday afternoon, many weekend tourists would be hurrying home, not alert to cyclists. He was especially concerned about drivers who drove intoxicated and tourists whose eyes were more on the scenery than the road. After explaining these potential road dangers, he proposed taking me past this dangerous place on their way home. His wife concurred.

In this way, I was helped past a dicey stretch of highway and saved me several days of highway riding in my quest to get quickly to the coast. Since my major focus was to ride on the beach, any highway riding was only a necessary step to get me to the beach—and around, past, or beyond any obstruction that might impede my progress on the sand.

Our drive together was made extra enjoyable because they were bike activists. They had spent years advocating and politicking for extending the Discovery Trail all the way from Port Angeles to the coast. Erik was on the Trail’s board, so he knew from personal knowledge all the roadblocks and hoops to get the trail extension approved and funded. Park officials and some vocal local people were the major opponents. It took two decades of advocacy and an act of Congress to get it approved. When finished, it will parallel Highway 101 on the bed of the historic Spruce Railroad and go on the west side of Lake Crescent on an old hiking trail. Hundreds of millions of dollars have been appropriated. Erik said, “It will be super world class.”

Our drive and conversation was so mutually interesting that Erik drove me twenty minutes beyond their house all the way to Forks—on the lame excuse that they needed to get their mail. As we bade our goodbyes in Forks, I let Erik take a spin around the parking lot on my bike. Carrie told me that she was certain that Erik would be talking all summer about wanting to do what I was doing. My parting words to him, “Erik, do it before you’re 67.”

As dusk was fast approaching, I decided to bed down in a cheap motel on the south end of town. Forks is the town for the setting of the popular Twilight novels. The town has been Twilight-ized. You can buy Twilight firewood or sleep in a Twilight-themed motel room. Whatever. The next day I safely left Forks without consequence. I guess if there were any vampires to be seen, they only lurked in the nearby woods.

Another thirty-five miles of good riding brought me finally to the coast. A tsunami evacuation sign four miles inland from Ruby Beach was the first indication that I was nearing the ocean. I had been forewarned by Erik that I wouldn’t be able to ride on this stretch of beach. It was regulated and patrolled by Olympic National Park rangers. Bike riding on their sand was not permitted. But I was overjoyed to finally be on the coast. I camped that night at the South campground, sheltered from stiff coastal winds by a jutting small bluff behind me.

The next morning I made for Queets, a river town on the north end of the Quinalt Indian Reservation. The Quinalt land encompasses a sizeable forest and some stunning coastal shoreline. They used to permit non-natives to take day hikes on their beach, but misuse of it caused them to withdraw those privileges. All my previous research and a conversation with a Quinalt Indian who stayed in the motel room next to mine in Forks, led me to believe I could cut across Quinalt land on a dirt road on the bluff above the beach. In doing so, I could avoid the long highway drive around the border of the reservation. That had real appeal. Thus when I came to the turn-off of the 4700 Road, I set off on a ride through the woods. It was most pleasant, but when I arrived at the Raft River’s log-jammed gulch, the bridge I was expecting to go across was nowhere to be found. I looked high and low and later learned from a Quinalt Indian that the bridge had been wrecked years before. So much for that.

Often it’s the mental part of bike touring that can get more discouraging than the physical part on tough days. This was one of those tough days. My “ditch” accommodations that night were rinky-dink, off the highway somewhere between Lake Quinalt and the small town of Amanda Park. Although the ride hadn’t been especially difficult, the disappointment in not being able to take the shortcut through the forest weighed me down heavily. Although I was in striking distance of the coast, I still had not ridden on the sandy shore. I had seen the ocean tantalizingly several times in stretches, but park and reservation regulations prevented me from riding on its shore.

Beset by these negative thoughts and self-doubt, I arrived on a drizzly morning at the small town of Neilton. It was to be one of my most memorable moments. It was here that I met one of life’s unforgettable characters—Fred W., a retired old mariner. I spent an unforgettable hour, standing out in a rainy post office parking lot, listening to Fred’s thoughts on the meaning of life. Fred’s speech was peppered with profanity. For Fred, it wasn’t a complete sentence without at least four or five F-bombs and assorted cuss words. It was so entertaining and profound that I asked him if I could tape record our encounter. He assented with a laugh, “Oh, I know! You’re writing a book aren’t you!”

Some of what he said had meaning for me at that very moment when I was doubting the wisdom of this whole bike journey. “I think that life is an exercise in suicide,” Fred said. “Find something that you like to do and let it kill you.” I like bike riding—a lot, but not to the point of dying for it.

I was beginning to wonder if my wife and brother had my number. My wife said I was insane for going on this bike trip. Echoing her, my brother must have said I was an insane idiot a hundred times for embarking on this adventure. My wife said I had just enough space on my helmet to write the word “Insane.” I assented to her wish and put “Insane” and “Insane Idiot” on the front and back of my helmet using stick-on letters. Was I an insane idiot for embarking on this ride? Fresh off a hard day, I was harboring a bucket load of self-doubt.

But Fred voiced another thought that also resonated with me. “I’ve always thought, you cannot die walking across the yard sitting at the kitchen table,” he said. “People sit at the kitchen table having too much coffee and cigarettes every morning. You know what they’re doing? They’re chicken [expletive]. They’re afraid that they’re going to die going across the yard.” Yes, I’ve always felt most alive when I’m out looking for adventure. Fred continued, “I want to die outside rather than plugged in to some [expletive] machine while the [expletive] insurance companies and quacks suck me dry.” Rock on!

After another half hour listening to more pearls of wisdom pour forth from the mouth of this salty old sailor and self-confessed doper, I took my leave with his words reverberating in my mind—some of which I recalled a few days later at a key moment of decision on my ride. Thank you, Fred.

A few miles later, I left Highway 101, taking a sharp right onto the scenic Moclips Highway. The road through this lush, moss-dripping forest brought me to a beach where I could finally ride my bike on sand. At the grocery store at Moclips, I happily swapped out my cleated pedals for flat pedals and set out in a burst of joy onto the sand. Yippee! I pedaled on the packed sand surface at low tide, swinging in a wide arc northward to the south bank of the mouth of the Moclips River. I made my beach camp here tucked into a jumble of big driftwood trunks and watched the sun set on the Pacific Ocean. This is what I came for!

I spent the next two days in beach-riding heaven: Moclips, Pacific Beach, Copalis Beach, Ocean City. I played with the surf, dodging in and out at random, sometimes without another soul in sight, sometimes joined by runners, an occasional surf fisherman, or passing beach-driving vehicles. But I was the sole bike rider—and everyone wanted to stop me, ask about my bike, and what kooky thing I was up to. At a few places, I drew a crowd. At these times, I felt a little bit like a rock star. But that got tiresome real quick. Same questions, same answers.

I crossed little and big creeks, on occasion having to ford them waist deep on foot, carrying my bike muscled on my shoulder. The Copalis River proved too deep to ford (and too cold) so I had to go inland onto the highway to get around it and then back to the beach south of it. It was a few miles south of the Copalis River that I found the strangest sight of my whole trip. From a distance it looked like a big shiny rock, but as I got closer, I saw that it was a huge beached whale, over 60 feet long washed clear up onto the beach way above the high tide line! It was on a remote stretch of beach. Did a rogue wave drop it there? A lone seagull sat in the sand looking at it, unable to puncture its thick hide—only the soft eyes pecked out leaving empty sockets. The smell? One needed to stay upwind.

Riding south of the whale, I was surprised to have my rear tire go flat. The wind was really whipping at that time and patching it while being pummeled by swirling sand was miserable. In retrospect now, I wonder why I didn’t just swap it out for my spare tube. Chalk it up to being the insane idiot. That night I slept in sawgrass dunes on the beach south of Ocean City.

That stretch of nice beach played out. It did go further south to the southern tip of the Ocean Shores resort, but I would have simply had to return north to take the highway around Grays Harbor. There used to be a private toll ferry that crossed over the mouth of the harbor to Westport, but it unfortunately went out of business. So I took the beach access road to the north boundary road of Ocean Shores and then got on S.R. 109 to work my way around the harbor.

Tourist season was in full swing. This highway was not built for bike travel and for the next five miles east of Hogan’s Corner I basically was forced to walk on the dirt shoulder because there was no paved segment of shoulder. The fast-moving traffic bordered on being not just dangerous, but frighteningly dangerous. This was doubly difficult because the long-thorned wild berries that grow like weeds beside roads in Washington and Oregon were strewn in my path.

I think it was during this stretch of “bike walking” that I mostly came to the decision to halt my beach ride at the Columbia River. I knew that I would face many more dangerous shoulder-less stretches of highway in Oregon and Northern California. This ride was simply not worth dying for to accomplish. Something that philosopher Fred said to me in Neilton kept echoing through my head. Fred said, “All I want to do is die like a man—barefoot, bald-headed without a tooth in my mouth, and very close to a woman that loved me. That’s how I hit this planet. What could be better than that!” Right again, Fred! I was feeling very vulnerable on these unsafe roads, both physically, and I guess, emotionally.

So when I got around Grays Harbor to Aberdeen, I gave my brother a call and asked if he could help me out on this next stretch. He was only 75 miles from there and agreed to come to his “insane” brother’s rescue. The next morning, he hauled my sorry self on S.R. 105 to Westport. I treated him to a good breakfast before he dropped me off at Westport’s popular surfing beach. I then rode down another beautiful 12-mile stretch of beach to North Cove, where my brother picked me up to haul me around Willapa Bay over to Long Beach peninsula. A sign over the access road to the beach at Long Beach touts it as being the “world’s longest beach.” He drove me up the peninsula to Ocean Park so I could ride this final stretch of Washington’s beaches. I bade him a brief goodbye and headed northward up the peninsula on the sand to find a place to bed down for a final night on the beach. It was a drizzly night and it seemed like my bivy leaked like a sieve.

Rain continued to dribble for most of the next morning and I had to pack up wet. But by mid-day the weather cleared and I enjoyed a nice finish to my 50-mile ride on the coastal beaches of Washington. The sand ended at Cape Disappointment, a fitting name for my aborted coast ride. But like explorers Lewis and Clark, I had made a discovery. My fat bike rode on the sand like a dream. The safest, surest, and speediest way to do what I had set out to do—ride on the beach from border to border—should be accomplished with a support vehicle. Oregon and California await. I’ve got the bike and the research on the ride-able beaches. All that’s lacking is another insane idiot to join me with a support vehicle to team up to do the rest of the journey.