By Mel Bashore —

For the last few years, every fall I have set off on a long bike tour. My wife’s “worry meter” always ratchets up a notch or two come September. She always thinks that this will be the ride where that semi with my name on its front radiator will find me.

In order to try to minimize her anxiety about this year’s jaunt, I put a bit more time into researching a route than I normally do. Last September I took a 1,000-mile solo ride from the Oregon coast to Utah (see Cycling Utah Fall/Winter 2011-2012 issue). In the course of that ride, I cut out a section of my planned journey when my wife reported that our doctor was moving up the date of her medical operation. To return home quicker, I traveled for hundreds of miles on Interstate 84—not the most ideal of routes.

This year I decided to tour on part of the route that I would have traveled last fall and vowed to travel as little possible on interstate freeways. I planned to travel north from Ogden to Salmon, Idaho. I had planned a loop route that would take me on different roads going up and back. Going north to Salmon, I would pass between the Beaverhead Mountains and the Lemhi Range on little-traveled Idaho State Highway 28. At Salmon, I planned on going south to home on U. S. Highway 93 through the Salmon-Challis National Forest. I planned on riding on highways and back roads and for less than twenty miles on interstate freeways.

Weeks before leaving, I kept abreast of the large Mustang Complex fire that was burning out of control in the Salmon-Challis National Forest. I looked at the National Interagency Fire Center website almost daily. About a week before leaving, it was reported that smoke was excessive, but a storm had cleared much of it from the area I was planning on riding. The weather and fire danger looked reasonable for my travel the day prior to my departure.

With fair prospects that I could safely reach my Salmon, Idaho, destination, I set out a week after Labor Day. I began my ride in Ogden on a pleasant fall morning, taking the back roads on the city’s west side to avoid traffic. As I went through Pleasant View, north of Ogden, an old farmer in bib overalls waved me over to the side of the road. He was curious, as many are, about my journey. I enjoyed our brief encounter and left him with a smile on my face.

It reminded me of the first day of a half-transcontinental ride that I embarked on four years ago when I took up long-distance bike riding at age 62. On that ride in 2008, my friend, Neil, and I started in Ness City, Kansas—two weeks after Labor Day. Our wives dropped us off in the middle of the United States and hoped, that if all went well, they would meet us in San Francisco six weeks later. They did, but I recall the feelings of trepidation and self-doubt that I started with on that journey.

We had hardly left tiny Ness City when a passing car pulled over on the roadside ahead of us. In the car was a Kansas farmer interested in our journey. He waved us over. We talked. He gave us a dollar and told us to split it on a beer. This was the beginning of many more memorable moments with other good people that we met along the way on that ride in 2008. It made me think that my ride in September 2012, with a similar beginning, might be a portent of good times ahead.

My memories went back to that first day on our ride in Kansas. After our nice meeting with the farmer, only a few miles further west, we pulled into a roadside stop to read a historical sign. Parked there was a Kansas highway department truck with a couple of men taking a mid-morning break. I struck up a conversation with them. They wanted to know where we were heading. When I told them San Francisco, the driver looked down at my fair-sized belly and asked, “Are you sure you can make it?” I told him thanks for noticing, but that I hoped that things would trim down by journey’s end. It did. The melon flattened as I lost 30 pounds in six weeks of riding.

Unlike that day four years earlier, I heard no frank or rude comments about my physique from anyone. But I did have some extra baggage (around the middle) that I knew I would lose on this journey. Long-distance bike riding for me comes with a seemingly guaranteed weight loss result. It’s almost formulaic. On every long ride, I have lost fifteen pounds for every thousand miles of pedaling. It has become an annual program. My wife fattens me up during the winter and summer (she is the world’s best cook)—and I take it off on my fall long bike ride.

After pedaling up “Fruit Way” on Highway 89 through Willard and Perry, I reached Brigham City. It was just 9:30 AM and too early to stop at my favorite burger joint. So I kept on going, enjoying a delightful tail wind the rest of the day. Traveling up Highway 38 just north of Collinston, I turned west on Highway 30 for a few miles. Then I turned north at Riverside on Highway 13 for some very pleasant rural riding. At Plymouth the road veered northwesterly and just west of the underpass of the I-15 freeway, I turned north on the frontage road. Anyone biking north in this part of Idaho should travel on this recently repaved old highway. I encountered only a handful of cars.

I reached Malad about 4 PM and asked directions to the home of old friends, Merrill and Sharon. It had been awhile since I’d seen them. I hoped to find them home, but had not called to alert them of my coming. Parking my bike on the front sidewalk, I stood on their front doorstep and rang the doorbell. Merrill came to the glass front door and peered out at me for a few seconds before shouting out, “Sharon! Sharon! Call the police quick and tell them there is a vagrant at our front door!” Always the joker! That night I enjoyed the comforts of a soft bed, delicious home cooking, and renewing old acquaintances.

When I told them my itinerary, they told me they had just heard on the news that Lemhi had been evacuated that very day due to the nearness of the fire. Merrill told me not to worry. He said that by the time I got to Lemhi, the fire would undoubtedly have been put out as he didn’t think there was really much to burn near there.

After a hearty breakfast of bacon, eggs, hash browns, and fresh fruit from their garden, I set out north out of town on the old highway. For a couple of miles, fence posts lining both sides of the road out of town were topped with old shoes and boots. It sort of reminded me of the “shoe tree” (near Middlegate, Nevada—unfortunately destroyed by vandals two years ago) that Neil and I had passed when riding on U.S. Highway 50.

After an absolutely pleasant day of riding on Old Highway 91, up and over Malad Summit, I passed through Inkom (we liked to call it Inkom Stink ‘Em when I was young). I was toying with the idea of pulling off up in the hills to bed down on BLM ground up Blackrock Canyon when a bike rider pulled up alongside and made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. Karma was with me. That night I showered at his place in Blackrock and bed down in his shady backyard.

I set out the next morning for Pocatello with a smile on my face. This tour was beginning in a beautiful way. But in Pocatello, I got some bad news. The fires were now seriously threatening along the route I wanted to take. Homes in the outskirts of Salmon had been evacuated. People in the towns of Salmon and Challis had been placed on one-minute evacuation notice. If I were to continue, I would be heading into a firestorm. I hadn’t set out with an alternate plan if things went awry, but right then I needed to come up with a Plan B.

I decided then and there that I would divert from my plan and head for Yellowstone—only two hundred miles to the northeast. September is a superb month to bike in the park. The tourist crowds have dwindled. Biking through the park in the fall is much safer than during the summer months. The weather is also generally still pleasant. The disappointment I felt in not being able to safely journey on my planned tour was easily dampened by the prospects of such an attractive alternative.

That night I bedded down on the banks of the Snake River in a free tourist park south of Idaho Falls. The next night I camped in the woods north of Ashton, a place where I’d camped a few years earlier when I’d ridden south from West Yellowstone. I choose to do what some other riders call “stealth camping,” but which I just refer to as “sleeping in a ditch.” Sometimes it has its moments, but I like the added sense of adventure it brings.

On the third day from having made my change in destination plans, I entered the west entrance to Yellowstone towards evening. In no hurry, I picked a good place to bed down on a narrow shelf above the Madison River overlooking the Madison Valley. The sunset was memorably spectacular, undoubtedly enhanced by the smoky haze coming from the big fires burning up central Idaho.

Biking along the Madison River into the park is very favorable. There are good shoulders and frequent pullouts. At the Madison junction, I chose to go north to the Norris geyser area in order to prolong my biking in the park. From Norris, I made the 12-mile crossover to Canyon in the park’s middle.

Generally I found the skies clear and free from smoke in the park except in this middle section. As I was climbing up the 8% grade, cars began bunching up just ahead of me. That is often a sign of wildlife. A few cars heading towards me slowed and the drivers warned me that a big buffalo was just ahead of me. As I rounded a curve in these thick woods, there he was, just fifty feet ahead. He was plodding steadily forward in the well-worn path next to the thin road shoulder. It seemed to me that his eyes took on a new shine, a new brightening of interest, when he spotted me. With the traffic slowed, I quickly decided to cross to the other side, and keep two lanes of cars between us. I have a feeling I’ll retain that moment when our eyes met for a long time in my memory.

That bison may have been getting away from a managed burn being undertaken in a part of that forest just south of the road. It was most interesting to see trees on fire just a hundred yards from the road—managed by trained brigades of protectively-clad firefighters. They used to call these forest fire-burning practices “controlled” or “proscribed” burns. I would suspect that they changed the terminology from “controlled” to “managed” burns to avoid the public relations snafus when such controlled fires occasionally got out of control.

That evening I ducked into some appealing woods south of Canyon to look for a good “ditch” to bed down in. As I rounded a little hillside, again just fifty feet ahead of me, was a monstrous brown hump with a twitchy tail—my second bison encounter of the day. Hearing me, he turned around, gave me a disinterested look, and resumed eating the grass. As he moved safely down the hill towards Hayden Valley, I set up my tent. I enjoyed falling asleep to the nearby sounds of bugling elk.

The next morning, I biked through Hayden Valley, stopping once to view two wolves guarding a buffalo carcass on the distant side of the Yellowstone River. I can attest that it is a different feeling one gets venturing through such wild places on two wheels rather than in the secure comfort of a car. Each night in the woods, I would place any food items I had in trees and at some distance from my tent. My food and I were never bothered.

I really enjoyed biking along the lake outlet of the Yellowstone River and along the shore of Yellowstone Lake. There were good road conditions with decent shoulders. I pulled off the road at Bridge Bay. In a nice, heated bathroom I decided to shampoo my hair. One of the drawbacks in “sleeping in a ditch” is the lack of bath and shower places. Although each night I clean up with some “baby wipes,” that isn’t the same as having a good shower. When I’m on the road, I at least try to have an occasional shampoo or spit bath in a convenient bathroom.

On this occasion, I had just finished toweling my hair dry when the door opened and in walked a tourist lady. She hadn’t paid attention to the sign on the door and barged in. We both had a good laugh and she backed out to go to the facilities next door. I was outside when she came out and we began visiting. She was from Delaware and was traveling through the park with her husband and friend. They were persistent in wanting to share some fruit and snacks with me. I was grateful for a fresh banana.

I would hardly mention this small kindness except for what happened two days later. I was then riding near the north boundary of Grand Teton National Park when I saw people excitedly waving at me from the side of the road up ahead. As I got closer, I saw it was my new friends from Delaware. The lady had a banana in her hand. How fun! I asked her husband if her door-sign reading had improved.

I had spent the final night in the park camped in the woods north of Lewis Lake. The previous day, I had stopped earlier than usual because it began raining lightly. I awoke to a foggy morning, which made for interesting riding along the shore of the lake. Just before embarking on the steep road bordering the Lewis River to the park’s south exit, my front tire went flat. I couldn’t recall another time when my front tire got a flat. It always seems to happen on the rear tire, but I’ve tried to lessen it from happening by using tire liners and thicker tubes. That has been a big improvement. I carry several new tubes on tours so I don’t have to expend the added time by repairing the tube on the road. I just swap out the tube, insert the new one, and later make the repairs to the tube when I get home. Before swapping out the tube, I checked the inner part of the tire and liner to make sure nothing sharp would cause further grief. I inserted one of those popular, but expensive tubes that have the green goop inside and claims to seal up any puncture hole. I thought this would just about end the possibility of any future flats on that tire. Wrong. Inside of forty more miles, my tire went flat again! I thought it must be a fluke because the green goop would certainly fill the hole. I pumped it up three more times in the next ten miles before finally pulling that expensive new tube in exasperation and putting in an ordinary new tube. While beside the road south of Jackson Hole, I vowed to let that company know how I felt about their “smart” product when I got home. I did. They were apologetic.

With those unpleasantries behind me, I took the nice bike trail almost to Hoback Junction where I stayed on Highway 89 going south through Star Valley. I slept that night on top of Salt River Pass off in the trees.

The next morning was chilly so I layered up to come off the pass. For better or worse, I chose to hug the Wyoming border south, although it might have been a bit more scenic to venture off to Montpelier and go north of Bear Lake. But I had ridden some of that road before and wanted to ride on some different roads. At Cokeville, I found that the road for the next thirty miles south was littered with skunk roadkill. It’s not an exaggeration to say that there were some stretches where I passed a dead skunk every 200 yards. When I got to Woodruff that evening, I went to bed with the smell of dead skunks in my nose.

At Woodruff, I made a poor decision. Rather than going up over the Monte Cristo Range, I decided to go south to Evanston and then down Echo Canyon to Ogden. I’d ridden that road over the Monte Cristos on Highway 39 before from the other direction. Again, my decision to take a different road (even though it would be 40 miles longer) was based on wanting to take a road I hadn’t ridden on before. My final day in the saddle was thus over a hundred miles and the prior day had been ninety miles.

When I think back now on the poor decision I made on my final day of riding, I picture a moment about ten miles south of Woodruff in bleak sagebrush land near the Wyoming-Utah border. The morning sun hadn’t yet warmed things up. I heard a vehicle slow down behind me. It was a pick-up truck with Idaho license plates. The truck pulled up alongside, the side window rolled down, and the truck matched my pace. Two bearded cowboys inside stared at me. They didn’t say a word. Just stared at me. I said, “Morning” and nodded my head. The driver gave a wave in salutation then off they went.

Strange encounter, but then, I must have seemed a strange sight to them—an old geezer riding a touring bike on a cool September morn in the middle of nowhere. It’s little events like these, of little moment or consequence, buried deep in my memory that will rise to the surface at the most unexpected time in the future. Guaranteed to happen. And that’s why I keep riding.

If You Go

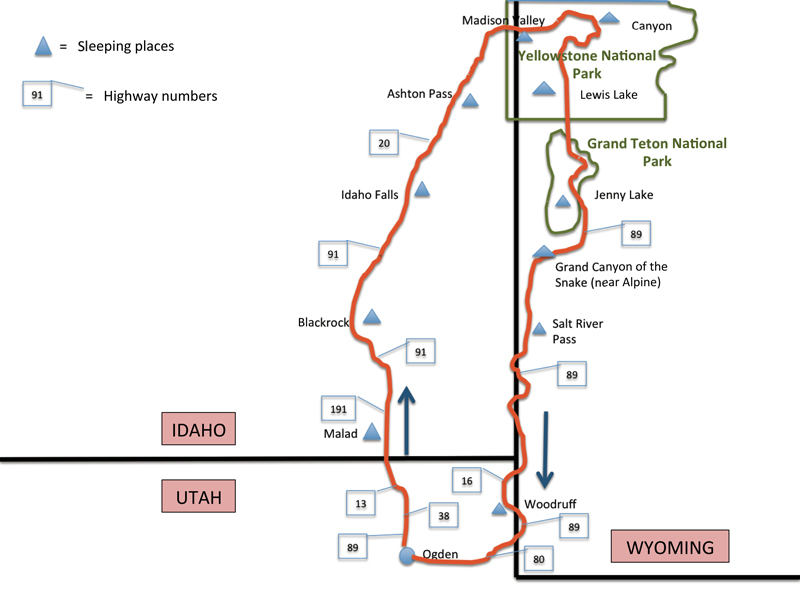

Start location: Ogden, Utah

Day 1 from Ogden to Malad, Idaho, 70 miles

Day 2 from Malad to Blackrock, Idaho, 60 miles

Day 3 from Blackrock to Idaho Falls, Idaho, 55 miles

Day 4 from Idaho Falls to Ashton Hill, Idaho, 60 miles

Day 5 from Ashton Hill to Madison Valley, Yellowstone, 55 miles

Day 6 from Madison Valley to Canyon, Yellowstone, 40 miles

Day 7 from Canyon to Lewis Lake, Yellowstone, 43 miles

Day 8 from Lewis Lake to Jenny Lake, Tetons, 55 miles

Day 9 from Jenny Lake to Grand Canyon of the Snake (near Alpine, Wyoming), 57 miles

Day 10 from Grand Canyon of the Snake to Salt River Pass, Wyoming, 53 miles

Day 11 from Salt River Pass to Woodruff, Utah, 85 miles

Day 12 from Woodruff to Ogden, 100 miles

Distances are close approximations

Food: peanut butter, Fig Newtons, MREs, convenience stores & burger joints

Camping: in a ditch