By Charles Pekow — In addition to providing transportation and recreation, the bicycle has impacted culture historically. The difference it made, in all its incarnations over time is chronicled in a new mini-paperback simply entitled bicycle (with a small “b), written by cyclist Jonathan Maskit.

The book is part of a series on Object Lessons from Bloomsbury Publishing Inc. that describes the histories and “hidden lives of ordinary things” we take for granted, ranging from golf balls to pregnancy tests to drivers licenses to dolls to sewers and so on.

While tracing the history of the machine and its relationship to the automobile, Maskit tells us a lot about his own personal experiences. A common theme in the book is that most of the infrastructure used for cycling wasn’t designed for it, even if it was retrofitted for it with the likes of bike lanes and signals. 19th Century bicycle prototypes had to share dirt roads with horses and buggies and since the dawn of the 20th Century cycles shared thoroughfares with larger and more-well armored automated vehicles and the bike rider has generally been at a disadvantage.

While tracing the history of the machine and its relationship to the automobile, Maskit tells us a lot about his own personal experiences. A common theme in the book is that most of the infrastructure used for cycling wasn’t designed for it, even if it was retrofitted for it with the likes of bike lanes and signals. 19th Century bicycle prototypes had to share dirt roads with horses and buggies and since the dawn of the 20th Century cycles shared thoroughfares with larger and more-well armored automated vehicles and the bike rider has generally been at a disadvantage.

The book can get technical in parts and refers to a lot of different scientists and philosophers to make points, even when they weren’t writing specifically about bicycling, as a universal truth can apply anywhere. The book sometimes digresses into talks about everything from gun control to maintaining sidewalks for pedestrians.

We also read some about other forms of transit, such as boats and trains, evidently to show how cycling fits into the overall transportation story. Efforts to put steam engines on bicycles flopped long before the electric bike caught on. We also get a technological explanation of how our muscles can power the wheels and how bicycles get built. And should anyone complain about cyclists on the road, you can tell them that many of the inventions routinely used in autos and airplanes, from pneumatic tires to carbon frames, were developed first for bicycles, which sped their use for automated transit. (The Wright Brothers, the author reminds us, were bicycle builders.)

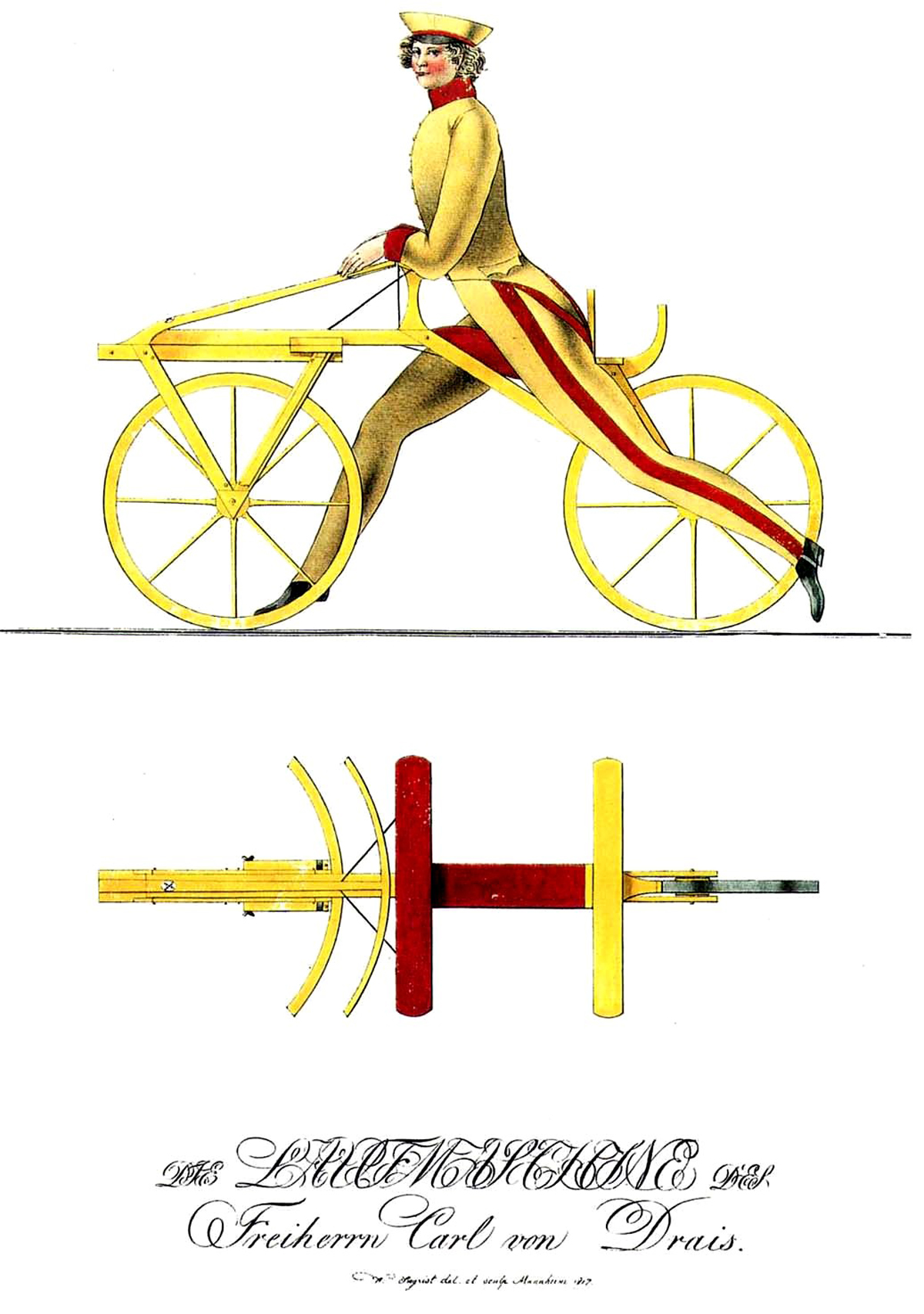

The book takes on a history of the forerunners of the modern bicycle. Maskit traces the origin to 1817 Germany, where people learned to skate during cold winters and thus learned the balance needed to pedal on two wheels. The cyclist scorned by an angry motorist today isn’t facing a new phenomenon: early riders weren’t welcomed in parks or by carriage operators not eager to share their space.

Though the bike (or its predecessors) never really caught on in Europe and North American during the 19th Century, it never completely went away. And designers gradually found ways to make them safer and easier to ride.

It makes cyclists proud to hear in the book that cycling is the most energy-efficient way to get around on land (the book doesn’t say so but only sailing can beat it). Long distances remain a problem, though.

Among the bicycle’s cultural impact, it became popular for late 19th Century women, freeing them from their costumes and making it easier for them to get around and unite, and even leading to their fight for suffrage.

In more modern times, Maskit tells us, largely through personal experience, about all the inconsiderate drivers, or those who don’t understand that bicyclists can use the roads too. He tells us of all the times drivers have made inappropriate gestures and even dumped exhaust at him. Thoroughfares between cities can be especially dangerous and unfriendly to bike on as they usually have faster speed limits. He goes on and on about auto crashes and sharing the road. He even tells us how the thoughts of enlightenment and political philosophers Rousseau, Hobbs and Locke apply to considering bicyclists’ rights to the road (something the philosophers themselves probably didn’t have in mind but their thoughts can be universally applied).

In fact, we get doses of philosophy sprinkled through the book, from Derrida’s reminder that we don’t control words (motorist, driver) to what 20th Century existentialists say about perception, which sometimes means drivers don’t see bicycles because they’re not looking for them.

Maskit makes some good points about the need to include more about bicyclists in drivers’ education. Let’s hope the people who can influence that will read the book and get the message.

The author also devotes a chapter to “ghost bikes,” memorials we occasionally (but once is too often) see along the roadways as memorials where cyclists came out on the wrong end of a crash; and another chapter to the movement to allow bicyclists to treat stop signs as yield signs. He promotes at length the idea that cyclists should be treated as equals with motorists under law and design. While “separate but equal” has been ruled unconstitutional for public schools, he suggests it would work fine for autos and bicycles to keep on separate paths to stay out of each other’s way, just as is common for pedestrians.

We also learn a bit about the history of police bike patrols. The book discusses but doesn’t resolve the fairly new issues brought up by of ebikes, scooters and whatever other new vehicles are complicating the scene. And while he notes that the COVID pandemic increased cycling, the book doesn’t deal with how some other factors affect ridership, from climate change to economics to energy sources.

Still, readers will learn much about how the bicycle has changed the world from the book.

Title: bicycle

Author: Jonathan Maskit

Published: Jan 25, 2024

Cost: $13.45 paperback; $10.76 ebook

Format: Paperback

Edition: 1st

Pages: 160, including 20 pages of index, bibliography, and footnotes

ISBN: 9781501338090

Imprint: Bloomsbury Academic

Series: Object Lessons

Publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing

URL: https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/bicycle-9781501338090