By Eric Ramirez — If you’re wondering what an air-spring is, or how it works, you’re probably not alone. Chances are that if you’re mountain biking you already have an intimate relationship with an air-spring. Most of our bikes come with a suspension fork and full-suspension bikes also come with a rear shock. Despite the brand of bike, it’s hard not to overlook the limited number of suspension manufacturers, such as Fox, RockShox, and DVO.

Photo by Eric Ramirez

How We Know the Air-Spring

The bumpy nature of mountain biking is felt chiefly in your pedals and handlebars. As you ride your new trail bike across any stretch of dirt and rocks, notice the harshness is smoothed out and sometimes makes the worst looking feature simply disappear. This behavior can be considered the over-simplified version of what suspension does.

While the wheels feel every nuance of the trail, your front and rear suspension units soften the blow by separating you from each large and small impact with a minute cushion of air. That cushion is the spring. Hence, the “air-spring,” for the purposes of this article.

The general feel of suspension might not lend enough clues to tell you if you’re using an air-spring. If you have an air-valve on either your rear shock or your fork, that’s an air-spring.

How Does it Work?

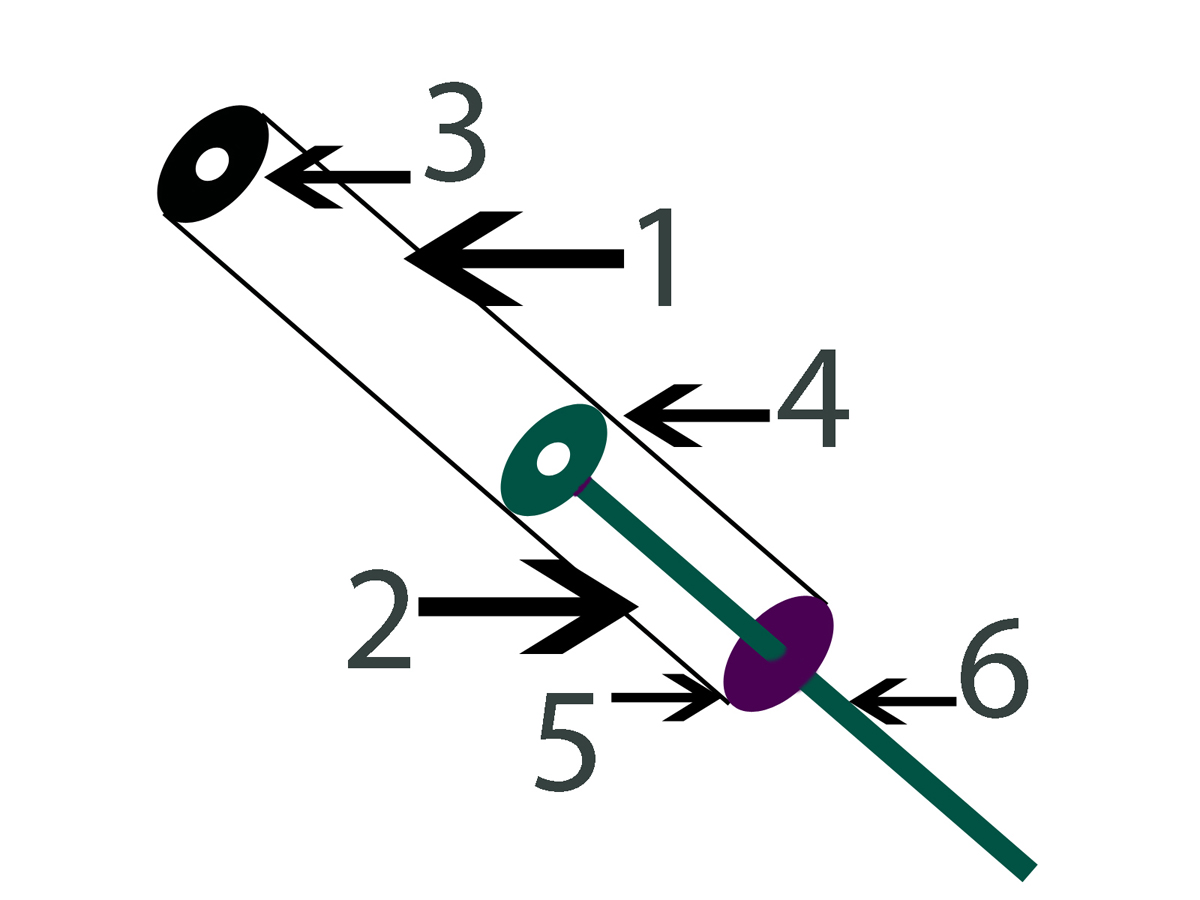

When we think of a spring, our minds often picture a wound-up wire that bounces, called a “coil.” Air-springs are different in many ways. First, a coil spring is capable of existing by itself. An air-spring without a dynamic container would simply be ambient air, and not a spring at all. In most suspension forks the air-spring container is the stanchion tube. There is typically one dynamic part of this container, which resembles a plunger.

This plunger cannot extend beyond a certain boundary of the container, but it can move into this chamber, able to compress the air inside. While not under load this compressed air resembles a barbeque propane tank, just wildly more expensive. The air continually pushes back against the pressure inside the chamber requiring a certain amount of external force to compress. By pushing the “plunger,” or “air-spring assembly,” into the chamber of air, it becomes an air-spring.

Break-Away

This act of initiating is called a compression cycle, also “travel,” and is referred to as “break-away.” Break-away force refers to the amount of energy it takes to get the travel started. If an air-spring chamber contains 68 psi of air, then it will require a certain amount of external pressure from rider weight or impacts to start moving: for example, a 120-pound rider sits on the bike. But the air-spring requires a bounce to get moving. This can have a harsh feel on the trail.

Newer suspension designs, like the Fox Evol (extra-volume) or RockShox Debonair (same thing), include an enlarged air chamber on the other side of the plunger head. This is called negative air. Manufacturers have engineered this chamber to absorb a given ratio of air from the main air-chamber.

Looking back to our 68-psi chamber, suppose the negative chamber has about 38 psi in it rather than 0 psi. Initiating a compression cycle is much easier because there is a 38 psi already pushing against the main air-spring. This improves the air-spring feel and suspension ride quality.

Ramp

As the compression cycle continues, the air-pressure increases exponentially. Whatever air is inside the chamber stays there, in a shrinking space. This compression of space and increase of pressure is exponential, which is why you hear bike people talking about “ramp.”

Imagine the pressure doubling inside the chamber every time the length is compressed by half. A rider might require 68 psi in their fork to support their riding weight and we can assume this is a 160mm travel trail fork. The rider hits a medium bump and uses half the travel. Half a chamber length reduction is a two-fold increase in pressure to 136 psi. At half travel there is 80mm left to full compression. If the length of the chamber is reduced by half again to 40mm remaining (where 120mm is used), the pressure of the air has again doubled to 272 psi.

| Length of Air Chamber (mm) | Pressure (psi) |

| 20 | 544 |

| 40 | 272 |

| 80 | 136 |

| 160 | 68 |

If you graph this information, a rudimentary chart would show the travel to internal air pressure ratio on a line that would be shaped like a ramp.

Inflation, Deflation, and Maintenance

In reading this, you might think about how much is involved in containing all this dynamic air pressure. Well, simply stated, there are tons of little seals in various types installed across the suspension units.

The air-spring itself has several seals that wear over time due to the constant pressure and cycling inside the air chambers. These will need to be replaced periodically. High-grade lubrication oils are used to keep the shock smooth and reduce friction. These must also be flushed and replaced periodically. When servicing suspension components, the technician should be checking the status of the air seals. Many technicians will insist on replacing the seals preventatively.

To avoid any erratic air-spring behavior, it is important to cycle your shock while inflating it, about every 20 psi or so. This allows the main air chamber to balance with the negative air spring. Never rapidly deflate the fork or shock, as this prevents the air in the negative chamber from evacuating; always deflate very slowly. Also, avoid deflating air-springs while loaded; air-springs should be fully extended when inflating or deflating.