By Eric Ramirez — You might think that the most representative connection you have to your bike is the saddle and handlebars. But, without forward motion that connection makes the bike more like your favorite arm-chair. No, the key connection to your bicycle is the pedals; as you drive them forward the gears and chain give you the momentum that makes you go. The stress of this motion results in wear on the drivetrain. As such, a large percentage of bikes that come to me for repair are in need of work on the drivetrain – I replace a lot of cassettes, chainrings, and chains.

Gears and Chain:

Imagine watching the pedaling motion from the drive-side of the bike, or the side with all the gears and chain. The motion of your foot driving you forward moves the crankarms in a clockwise, circular direction. In fact, you are driving a metal circular gear called a chainring. Zoom in and imagine the teeth of that chainring pulling the chain into orbit around the gear and hence pulling the bike forward. The leading edges of those teeth are taking the brunt of the force that you exert.

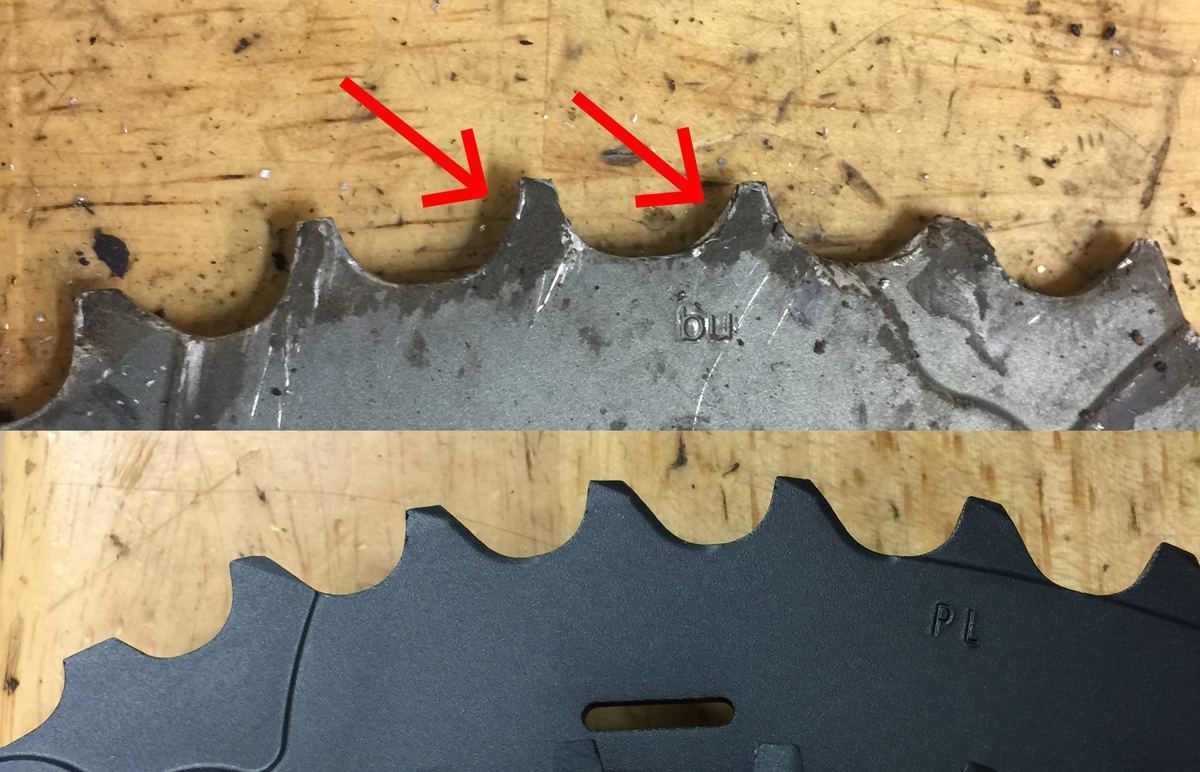

As long as the chain is within reasonable wear limits, it will not prematurely wear out the teeth of the chainring. However, over time wear is inevitable. The sheer pressure of the teeth pulling that chain forward slowly mashes those metal teeth and they deform in one way or another. As the chain starts to wear and effectively “stretch”, the wear on chainring teeth is exacerbated. Chainring design attempts to compensate for this with the use of stronger alloys or coatings, cold forging or stamping, but eventually all succumb to the erosive force of use.

The same thing happens to your cassette – the gear cluster mounted to your rear wheel – only faster. The teeth of these gears will see the mashing effect on the opposite side; this is very apparent on an older, worn cassette.

Often, within just a few rides, an overly-worn chain may break. Chain wear is without a doubt the quickest type of wear on a bicycle. New drivetrain systems with 11 and 12 cog cassettes, or speeds, have a greater width across and thus require greater lateral chain movement.

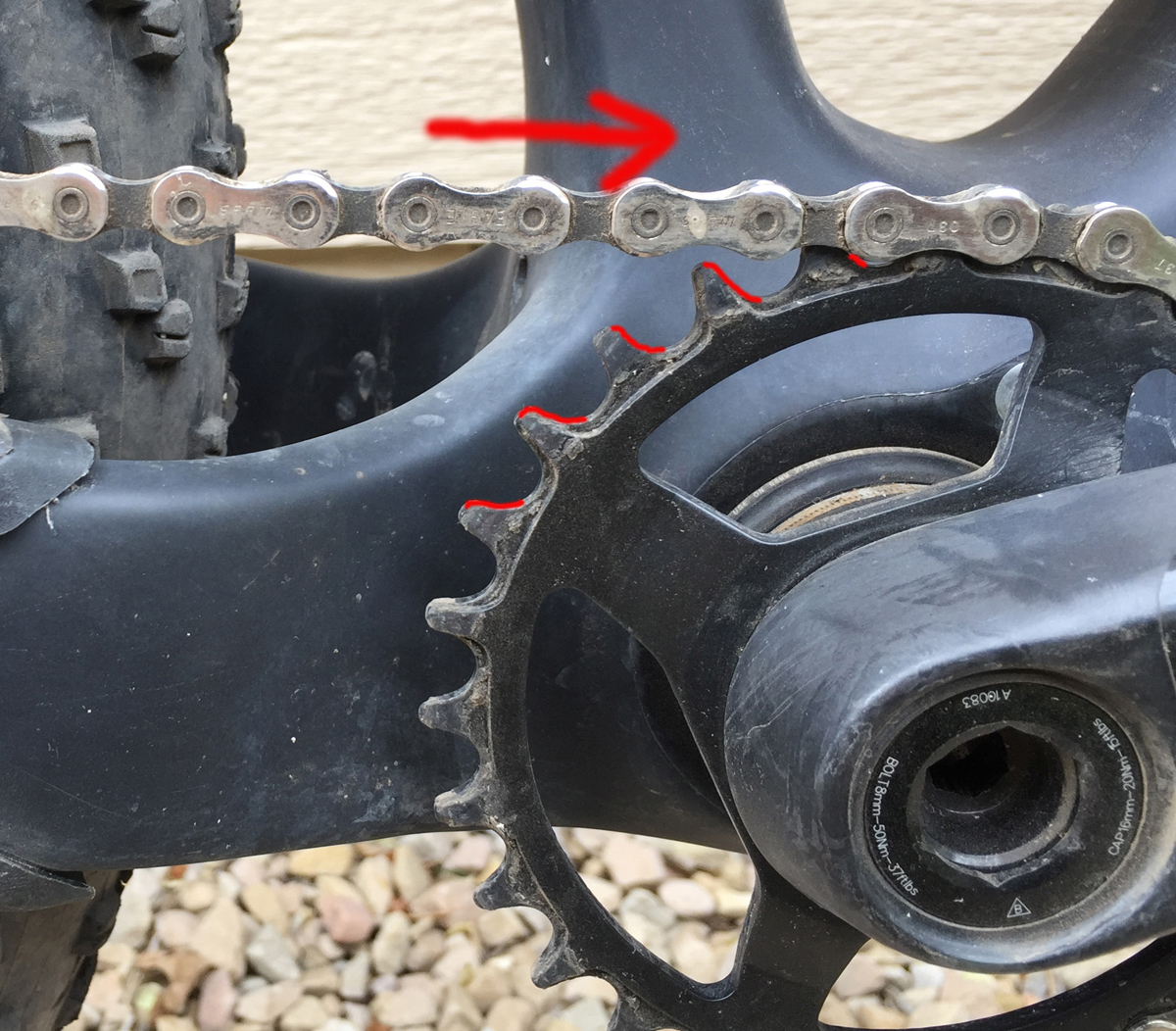

The chain has minimal stress in gear combinations that allow it to travel in a straight line. But, this is often not the case. In the easiest and the hardest gears (respectively the largest and smallest cogs), a chainlink departs on its journey from the cassette traveling above the chain-stay to the chainring under the load of the bike and rider. Looking down from the saddle, the chain is laterally twisted as it leaves the cog and arrives at the chainring. Here, the chain is under the most stress since this is not a natural, straight-line motion.

When mechanics talk about “chain stretch” they’re referring to the wear caused, chiefly, by this motion. The plates of the chain chew at the pins and vice-versa. As this wear progresses, it will continue to degrade the drivetrain gearing at an accelerated rate. Something will give; usually it will be the chain.

The Fix: (A Shop Scenario)

The chain is broken. We examine the break and it is clearly from wear. We replace the chain, or at least plan to. On a test ride it is discovered that the chain will not shift cleanly from cog to cog and under load the chain literally skips forward on the gear (under pressure the chain will jump a space ahead). Then, the chain gets sucked up on the chainring going for another revolution. This action can nearly break off the rear derailleur as the chain tension ramps up.

At this point it is clear that chainrings and cassette need replacing. The cost of this adds up quickly, especially on higher-end road bikes. Replacing these parts will generally fix the issue. However, a fancy chainring will last a very long time offering easy maintenance and shift quality if the chain is regularly replaced.

It is worth mentioning that other types of stress can cause a chainring or cassette to need replacing prematurely. Part of the shifting process consists of the chain hopping on to ramps and pins on chainrings and cogs to physically shift up the range. If a derailleur isn’t properly adjusted or shifting is very hard or aggressive, these ramps and pins wear down and shifting becomes extremely difficult. Gear replacement is the only fix.

You and your mechanic will be able to find the most reasonable fix. Sometimes, replacement options will be limited depending on availability of replacement parts. Generally, there are more options than ever and you’ll usually be able to find something that will work well and save you some cash. The best option usually matches the hardware you already have. That, however, is not always the most economical.

Mileage:

Folks often ask me how many miles they can expect to get out of a chain. My response is, unfortunately, ambiguous. There is no clear answer for this since every rider varies in weight, riding style (sprinting, climbing, long, flat-out, mellow, racing, etc.), terrain preference, and equipment choice. But checking the wear on the chain with a simple chain length gauge will help to know when the time has arrived to replace it. The information in this article will help you to know if other things need replacing too.